Four central districts and Turkey’s nationalist voters will define the battle for the country’s capital

Can he do it? Commentators and what’s left of Turkey’s Twittersphere is alight with the speculation that the long-anticipated defeat to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan will come not in Istanbul, the jewel in the crown of Turkish local politics, but in conservative Ankara.

Here, the main opposition CHP made a tactical swoop to the right by fielding Mansur Yavaş, the man who contested the previous election for the main nationalist party.

Mansur Yavaş needs to persuade 9% more of Ankara’s voters

As far as the campaign is concerned, the gamble has paid off. The AK Party has been rattled enough to launch personal attacks on Mr Yavaş’s credibility after he switched parties. AK campaigners are alleged to be behind fake posters depicting him embracing Hüseyin Aygün, a left wing MP to whom he is known to hold quite opposite views. And the AK candidate, Melih Gökçek, has even claimed fraud with be rife on polling day.

Whether the gamble will translate into votes is another matter.

Boundary changes

Mr Yavaş came a close third as the MHP mayoral candidate in 2009. This year, he needs a swing of 9% from the MHP to win the mayoralty. That’s nearly one in every ten Ankara voters switching to the CHP.

That might seem achievable enough, but Ankara’s two-horse race is generating the same media and internet interest that Istanbul’s did in 2009, so it’s inevitable Mr Gökçek will improve on his 2009 result too. It’s plausible that MHP voters angry at Mr Yavaş’s defection will support Mr Gökçek against him.

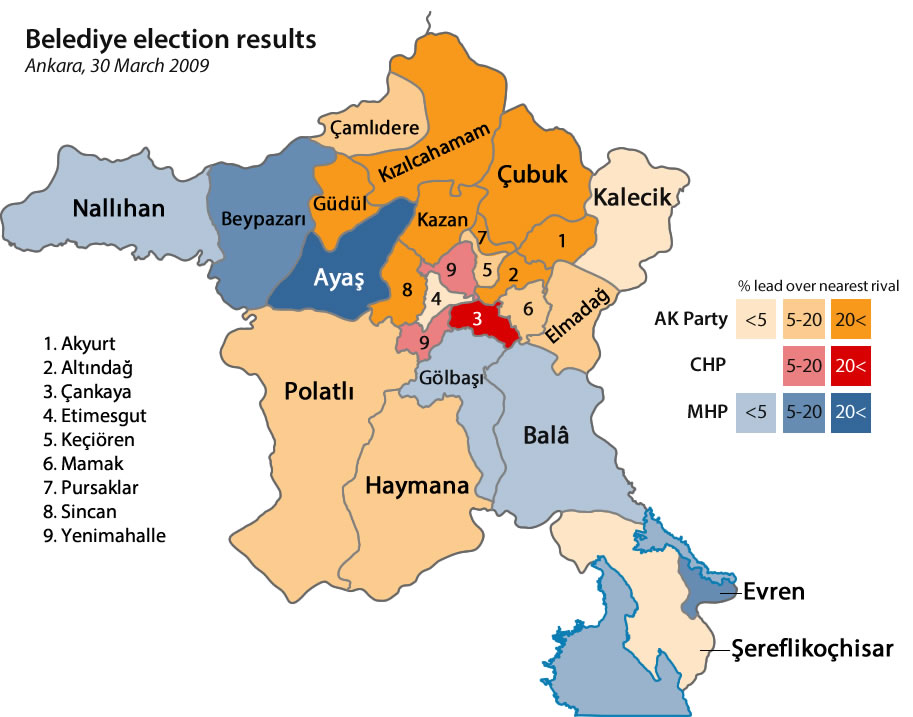

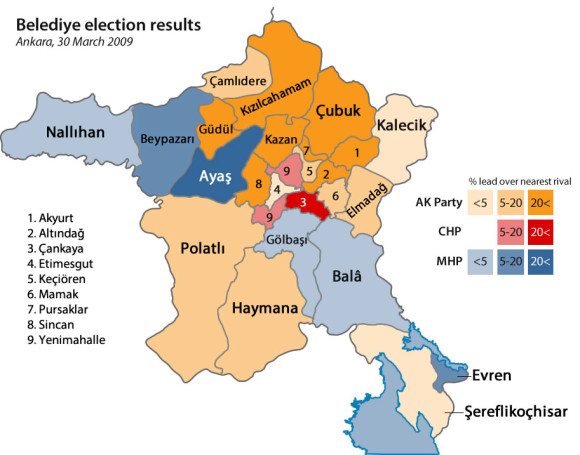

As a result of boundary changes, this election will see 200,000 new rural voters electing the mayor of Ankara in addition to the 3.6 million living in existing Büyükşehir districts. Proportionally this quite different to places like Mardin and Ordu, where new rural votes vastly outnumber those from the old town.

Although every vote is important in a race as close as this one, the race in Ankara will be decided in the more populous central districts.

Half of voters in four marginals

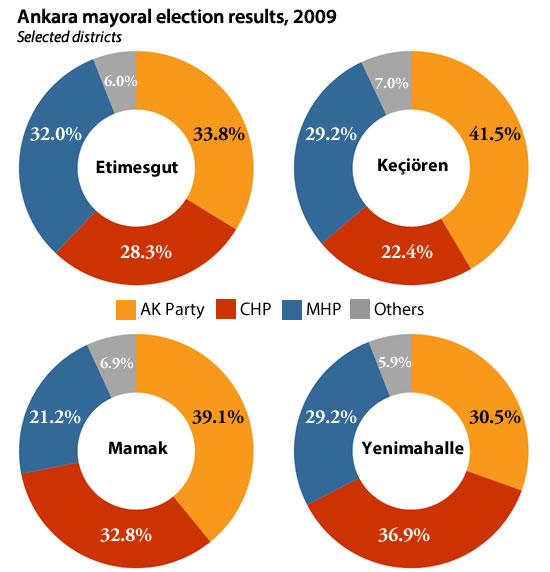

Etimesgut, Keçiören, Mamak and Yenimahalle account for just under half – 49.3% – of voters in Ankara. These districts produced the closest battle between the three candidates in 2009. It is here that Mr Yavaş will have to attract as many MHP voters as possible to his new party.

- Etimesgut (327,211 registered voters in 2014), to the west of the city, was the closest race of them all five years ago. Just 5 percentage points separated the first-placed AK Party and the CHP in third in the city-wide mayoral race. For the district, it produced an MHP mayor – just.

- Like Etimesgut and much of northern Ankara, Keçiören (609,900) is predominantly conservative. It is strong AK Party territory, so much so that the prime minister’s Ankara house is here.

- To the east of the town is Mamak (402,276). This geographically large district is home to many of the Anatolian migrants who have settled in Ankara over the last two decades. Inner neighbourhoods tend more towards the CHP in the south and AK in the north. Like Keçiören, it has an AK Party mayor

- Yenimahalle (435,579), founded as an out-of-town retreat for civil servants and their kin in the 1950s, half-encircles Etimesgut and reflects some of its divisions. Again, pro-CHP in inner town areas; more conservative outside and to the north. These divisions produced a CHP district mayor in 2009.

Polling trends

How successful will Mr Yavaş be at attracting conservatives in these four districts to his rather than Mr Gökçek’s camp?

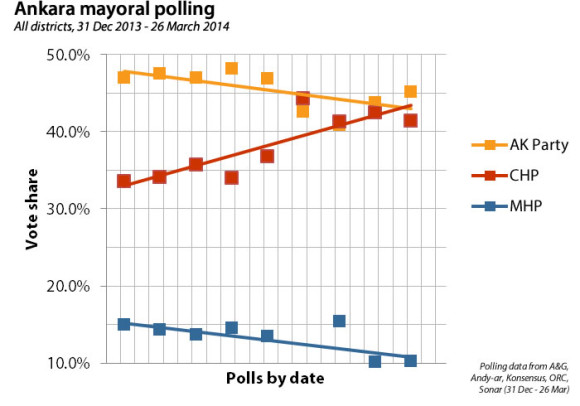

Polling in Turkey is notoriously unreliable. Data for any Ankara district, let alone the four marginals, is scant on the ground. The limited polling that is available varies wildly in predictions, methods and reliability.

ORC, for example, confidently predicts a comfortable Melih Gökçek victory with 46.8% with Mansur Yavaş trailing by 10 percentage points. Konsensus, on the other hand, believes Mr Yavaş will pip his AK rival to the post, 44.4% to 42.6%.

A slightly more reliable indicator of voting trends comes by looking at how their poll results have changed since December.

All polling companies have been showing a narrowing gap between the two main parties in Ankara since the New Year. This will be a very close result and – it almost goes without saying – far too close to call.