Turkey operates two parallel systems of local government, making it appear labyrinthine even to most ordinary voters. The İl Genel Meclisi (special provincial authority) is the most confusing of the lot.

Local government in Turkey is organised inside each of the country’s 81 provinces. Power is shared among two bodies: councils (belediye) and mysterious organisations called special provincial authorities (il özel idaresi).

Councils do what they say on the tin: rubbish collection, transport planning and plenty of billboard posters bearing the Mayor’s earnest face. They’ve existed in Turkey since before Atatürk’s time. But what about the latter?

An embassy at home…

Provincial authorities can trace their roots to the first efforts to codify an Ottoman constitution. In their current form, they are a post-coup creation and can be best described as a Turkish embassy inside a Turkish province. They exist because the military government that followed Turkey’s 1980 coup wanted a way for central government to keep a hold on security in the provinces once the state of emergency was lifted.

It is headed up by a governor (vali), who is appointed from Ankara and has the vague job description of executing ministerial orders in the provinces. In practice, this means his job (and it is “he”; there have only been two women governors in thirty years and 81 provinces) is mostly to order the police and army about.

This is why Avni Mutlu became so prominent in the summer of 2013. As governor of Istanbul, he was responsible for sending police officers onto the streets so as to “maintain his province’s security” during the Gezi Park protests. He withdrew them from Taksim square when he was ordered to do so by central government in Ankara. He sent them back in following a similar order.

…with a democratic tinge

Governors are civil servants and ostensibly non-partisan. But a change of government in Ankara inevitably leads to governors in some of the more important provinces being replaced with political allies. Many eventually end up in politics and government – such as Muammer Güler, Mr Mutlu’s predecessor, who became an interior minister.

Despite this, provincial authorities do have a democratic element. Each authority has an assembly with a number of seats that corresponds to the province’s population. Istanbul’s is the largest – with 277 seats – while Bayburt in northeastern Turkey has an assembly of just eight.

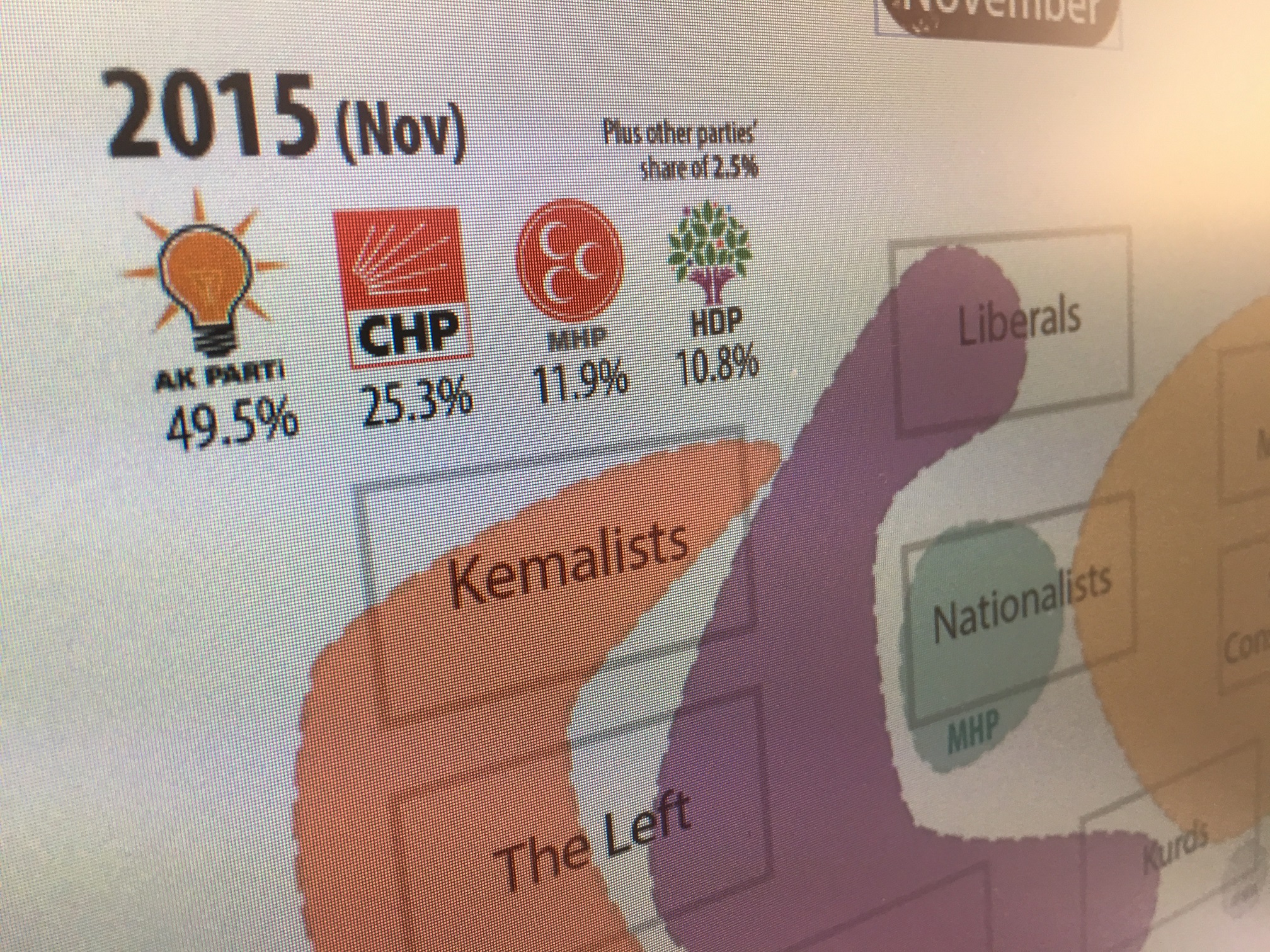

When voters elect their new mayors and councils, they also vote for a party to represent them on their provincial assembly. Assembly members are elected from a party list. It’s a proportional voting system – the party with the most votes gets the most seats – but, as with parliamentary elections, a party must cross a 10 percent national threshold before winning anything.

These have absolutely nothing to do with councils: any decision they pass is sent to the governor, not the mayor, for approval.

Authority no more

But provincial assemblies have been abolished in all Büyükşehir cities, meaning the majority of Turkish people won’t be electing assembly members. Of the plethora responsibilities held by the assembly, some will be handed to councils, others returned to central government – and a substantial number will remain with the unelected governor, whose position has remains intact.

The removal of the assembly as a check and balance function on local governors – such as it was – is another example of the rapidly degenerating concept of power separation in Turkey.