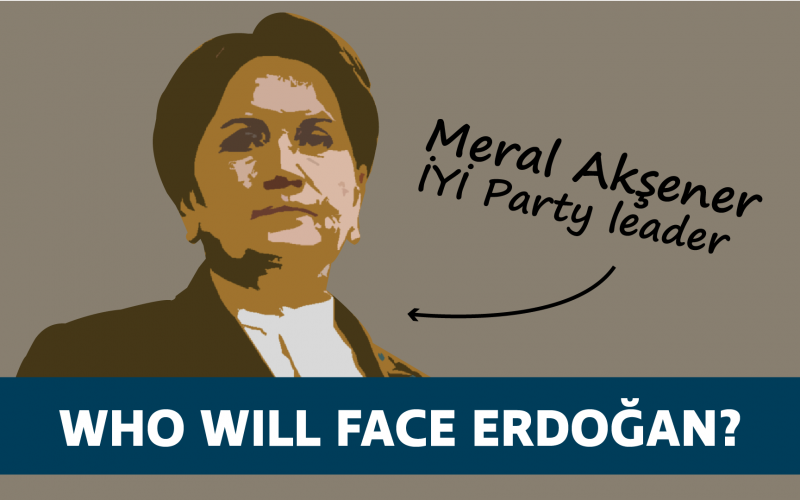

If Meral Akşener ever achieves her self-declared dream of becoming Turkey’s next prime minister, she would not be the first woman to hold that office – but she would certainly be the first to reach it through sheer ability.

The Good (İYİ) Party leader stunned many in September 2021 when she ruled herself out of the running for the presidency.

Instead, she said, she wanted to restore cabinet government in Turkey and place herself in charge.

She has been adamant since then that she won’t change her mind — but her party would like her to, and so the possibility can’t be ruled out.

When İYİ was launched in 2017, this website called Akşener a rarity in Turkish politics because she is a confident, outspoken conservative with experience in government – but not with the AK Party.

That distinctive quality makes her one of the country’s most recognised politicians. Little wonder this website has written extensively about her – most prominently, the government’s repeated attempts to draw her to their camp. (She’s rejected those even more strongly than she the possibility she’d change her mind about a presidential bid.)

Coming from a nationalist background, she struggles with the concept of minorities and divergent ethnic identities.

Yet it’s telling that the imprisoned Kurdish leader Selahattin Demirtaş singled her out back in 2020 as the politician he’d most like to visit unannounced for a friendly breakfast.

He picked her because of Akşener’s political background, knowing perfectly well that the idea of a Kurd and Turkish nationalist having breakfast is a controversial one.

It also reveals Demirtaş considers Akşener is someone he could work with.

This is perhaps why the best question to ask about the İYİ leader is not whether she will change her mind and run, or whether she could win, but why she’s chosen to rule herself out.

The job that she covets – prime minister – doesn’t exist any more, and the constitutional changes needed to reinstate mean she’s at least two elections away from leading a cabinet government.

Those changes would involve turning the presidency into a compromising, moderating role with very few actual powers, which is a job she doesn’t want for herself.

It’s far from clear that her movement will ever grow large enough to deliver victory in a parliamentary election but, plainly, this 66-year-old plans to stick around in politics for some time.

That’s unlike, say, CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, who at 74 will probably fight his last election this year and could see out a happy retirement in the presidency.

As with all the main opposition contenders, polls suggest that she were the sole candidate again Erdogan, she would probably win.