It is not often that a waiter asks to borrow a book as you’re reading it.

I was sitting in a café in Ankara’s Tunalı Hilmi a couple of years ago, having just raided the bookshop across the street for several titles about Turkish nationalism in the 21st century.

The face of Meral Akşener, struck in thoughtful pose, was looking up from the covers of one – it was a new authorised biography of the nationalist Good (İYİ) Party leader by Vedat Erbaş, an academic.

The waiter asked if I wouldn’t mind him skipping through it while I had my tea.

Ms Akşener interested him, he said: “She understands who we are and what we’ve been through.”

The waiter, a social conservative on a modest salary who could not have been older than 20, was one of them.

I never got to ask, but I’m certain he learned about İYİ’s leader by following her on social media: it was not as if she attracted much coverage in the mainstream press.

Fast forward to now, two years almost to the day since my visit to that café, and Ms Akşener is still in the news. In fact, on Monday alone, there were three different stories directly concerning her:

- She revealed the government was investigating Istanbul’s mayor over his opposition to President Erdoğan’s Kanal Istanbul project;

- Her party expelled one of her deputies, Ümit Özdağ, over apparently unsubstantiated allegations he made about an İYİ official;

- She discussed plans to reinstate a parliamentary system in Turkey with former prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, who leads another opposition party.

A busy and not entirely positive day for her, but one which demonstrated how successful she has become at entering the national consciousness.

These days it is almost fashionable to be an İYİ supporter, and few would argue it is not an electoral force to be reckoned with.

Its national showing in 2018 was impressive for a fledging party; in the following year’s local elections, its support was crucial to the governing AK Party’s defeat in major cities like Istanbul and Ankara.

A soaring record

This may have been a movement founded by disaffected members of the nationalist MHP, but it now appeals to a far wider electorate.

Much of the success is down to Ms Akşener herself: few Turkish politicians today – certainly no other party leader – are as gregarious.

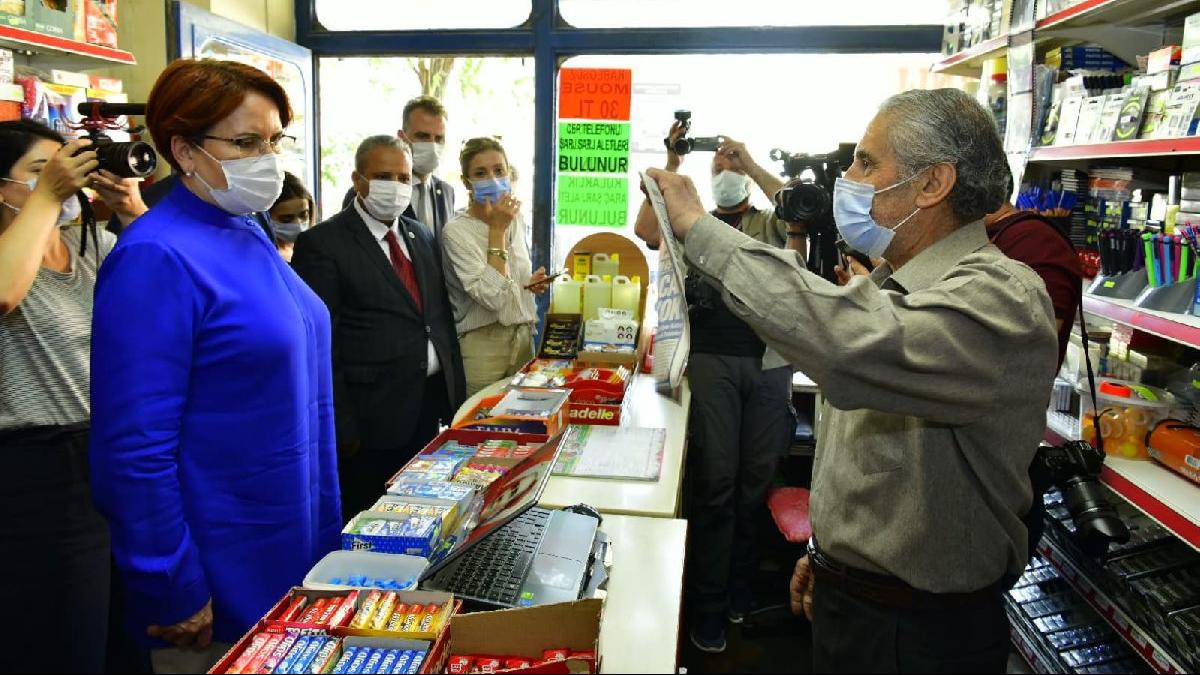

She has spent much of the year on a protracted tour of the country, making a point of meeting business owners to discuss their strife, and making sure she is filmed doing it.

Yet she comes across not as superficial but genuine, sometimes even funny, on social media, even when her face is concealed behind a coronavirus-impeding mask.

It appears to be paying off: in the summer, İYİ overtook the pro-Kurdish HDP in JamesInTurkey.com’s poll of opinion polls as the third-largest party by voter intention.

Ms Akşener is personally popular too. One recent poll found she was the most effective opposition leader not just among İYİ supporters, but those who support for other parties.

.@turkiye_raporu Ekim ayı birinci raporundan bir sonuç. En iyi muhalefet kim? pic.twitter.com/Nbrh7qV8ul

— Can Selcuki (@CanSelcuki) October 20, 2020

She has another quality: uniquely in Turkey’s polarised political climate, every major party covets her.

There have been repeated attempts by the governing AK Party and the MHP, its de facto coalition partner, to lure Ms Akşener away from the opposition to their camp.

It’s a similar story with the opposition: she of course gets on well with Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu’s CHP, İYİ’s electoral alliance partner, but the still-imprisoned Selahattin Demirtaş too caused waves a few months ago when he singled her out as the politician he would like to visit unannounced for a friendly breakfast.

That’s quite remarkable: even though the nationalist Ms Akşener struggles with the concept of minorities and divergent ethnic identities, the former leader of Turkey’s biggest Kurdish movement sees, in her, someone they could work with.

Where now?

To all these overtures, the İYİ Party leader’s response has been a political balancing act: she remains a government critic, but doesn’t explicitly rule out throwing her lot in with Mr Erdoğan either.

All the signs so far are that Ümit Özdağ’s eviction is a show of Meral Akşener’s strength, not a sign of her weakness.

Her party is easily the most dynamic force in Turkish politics at the moment.

An analysis to follow on https://t.co/JqER6GwKDI soon.

— JamesInTurkey.com (@jamesinturkey) November 16, 2020

Her main condition appears to be regime change. If the AK Party and MHP were to accept a return to a parliamentary system – admittedly, a very high bar – she could be on board.

Far likelier is that Meral Akşener will again be an opposition candidate for president and İYİ will retain its alliance with the CHP at the next election.

What will change, particularly if her popularity continues to tick upwards, is how much influence her party will have over a future government.

One to watch.