Is 13 years without a win too long to lead Turkey’s main opposition party? That’s what his critics say and the figures do speak for themselves.

In the 2011 election, the year after Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu became leader, the CHP took 26% of the vote and was the only party to increase its tally of seats.

At the most recent election seven years later, it won 23% and its number of seats barely changed.

The critics are circling: the party has been treading water for years, they say. Yet that charge is harsh — for two broad reasons.

First, it ignores the CHP’s desperate state under Kılıçdaroğlu’s predecessor. Deniz Baykal’s party was a reactionary rump run by the very secularist elites that Turkish voters overwhelmingly rejected at the turn of the century.

Kılıçdaroğlu drove the party towards the centre ground, engaging nationalists and conservatives in a bid to offer an alternative to the AK Party. That was no easy task: it involved ejecting many of the old guard, often kicking and screaming.

Second, Kılıçdaroğlu’s wide-tent strategy did deliver some popular success.

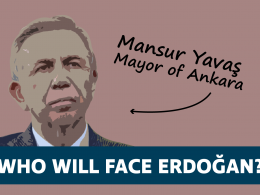

Ekrem İmamoğlu and Mansur Yavaş owe their mayoralties to him. Movements like Meral Akşener’s İYİ Party owe their very existence to his clever politicking.

Millions were inspired by his decision to March hundreds of kilometres between Turkey’s two largest cities to protest against the eroding justice system. And it was his idea to unite six opposition parties into a coherent anti-Erdoğan movement.

So why has his strategy delivered nothing more than silver medals in four successive general election?

For his critics, the reason is Kılıçdaroğlu himself. The CHP leader is too mild-mannered and reserved, they say, to give voters something to be excited about.

Yet that view is mostly the handiwork of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who has spent years tarring Kılıçdaroğlu as inexperienced, elitist and incapable of representing the interests of conservative voters.

Those characterisations are all unfair — worse, they disguise the CHP leader’s true flaws.

Chief among those is Kılıçdaroğlu’s judgment: for all his clever politicking, the last decade contains more than a few moments when he simply made the wrong call.

For example, it was a mistake to nominate a man even less charismatic than himself, the pious Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu, as the cross-party candidate for president in 2014.

It alienated CHP supporters — and Erdoğan trounced him anyway.

In 2016, he backed a government move to remove parliamentary immunity for scores of MPs – mostly those with the pro-Kurdish HDP.

Many were arrested and convicted on terrorism charges, including the party’s ex-leader Selahattin Demirtaş, who is still in prison.

More recently, he was in the United States, not in parliament in Ankara, when MPs voted through a new, restrictive censorship law.

And when his mayor of Istanbul was convicted of insulting public servants and banned from politics, Kılıçdaroğlu was in Germany.

Neither event was a bolt out of the blue, and yet the CHP leader’s knack for being in the wrong place at the wrong time hasn’t gone unnoticed. Some say he is poor at sensing the public mood.

Yet Kılıçdaroğlu would likely make a good president.

His sensible leadership of the CHP shows he would be even-handed, listen to unpopular opinions and be prepared to take difficult decisions. Turkey needs a leader who is mild-mannered and reasonable to follow two decades of the divisive Erdoğan.

But a good potential president does not necessarily make for a good presidential candidate.

For a man who has never been elected to public office, polls suggest the CHP leader is staggeringly unpopular – and a lot of that is Erdoğan’s fault. The colours he daubed on Kılıçdaroğlu have stuck, perhaps irreparably.

And yet Ankara’s worst-kept secret is that he wants to offer himself to voters in place of Erdoğan, the man who has shaped 21st century Turkey in his image.

Whether he runs or not, it seems like this general election will be Kılıçdaroğlu’s last. If he runs, it will be quite a gamble.