“Message received. We will do what is necessary,” Binali Yıldırım, Turkey’s prime minister, said to the crowds chanting for the death penalty at a rally just hours after last year’s coup attempt was thwarted.

It was a response that quickened the pulse of the Turkish opposition and European observers alike: could Turkey really be on the verge of reinstating the noose?

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan seemed to think so. At rally after rally over the past year his speeches have been interrupted by the braying call idam isteriz (“we want the death penalty”).

Each time the president of Turkey would assure them that they did not have long to wait.

Asked to explain his stance in television interviews, like this one with CNN International, he said that if parliament passed a bill to reinstate capital punishment, he would sign it.

Mr Erdoğan repeated that position at an early-morning rally to mark the coup’s anniversary outside parliament on Sunday. Once again, the crowds chanted for the death penalty.

Once again, the president said he would sign it if the building behind him approves it.

EU no more

The European Union has been uncharacteristically firm.

“I told him: If you reintroduce the death penalty, then it’s time to end,” European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker said he told Mr Erdoğan during a recent conversation.

He was referring to Turkey’s EU membership talks, which notionally still continue but are in reality going nowhere.

That might be precisely what Mr Erdoğan wants: he told the BBC last week that he would be “relieved” if the European Union decided to call it off.

How would it work?

Despite all the bluster, Turkey’s governing AK Party has not yet presented a capital punishment bill to parliament.

There has been remarkably little chatter about what form that bill, if ever introduced, might take.

First, the government would need to amend the Turkish penal code to define the crimes that would subject to death penalty.

Until the turn of the century, this was covered by code 765 and included the following crimes

- murder

- crimes against the constitution

- waging war against the state

- destruction of military facilities

It’s quite clear to see how these would cover anyone the government deems to be a member of the Fetullah Gülen network for acts committed on the night of 15 July 2016. It would apply to a fair few Kurdish militants too.

But wait, there’s more

The crimes above are some of the gravest anyone can commit against a country anywhere in the world, but the penal code didn’t stop there. For example:

- Revealing information that threatens national security

That is precisely the charge faced by journalist Can Dündar in absentia right now. Reinstating the death penalty precisely as it was when it was abolished would mean reporting leaked information becomes a capital offence in Turkey.

Conjure up some new crimes

Of course, there is nothing yet to suggest the AK Party would simply reinstate the rules they themselves abolished a decade and a half ago.

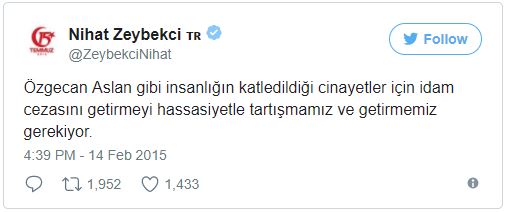

That raises the prospect of an intervention from the likes of Nihat Zeybekci, the economy minister, who tweeted in response to the brutal assault and murder of a 20-year-old woman in 2015 that “we need to discuss and introduce with sensitivity the death penalty for murders where … humanity is massacred”.

And someone will have the gruesome task of decide how to execute the convicts. Do they bring back the noose or go down the lethal injection route?

Constitutional hurdle

But it isn’t just about the penal code. The government would also have to amend the Turkish constitution to repeal an amendment to Article 38 that it itself introduced in 2004: “Neither death penalty nor general confiscation shall be imposed as punishment.”

The AK Party does not have enough seats in parliament to pass that amendment alone. The nationalist MHP is straining at the leash for the death penalty and can provide the numbers – but only to put the proposal to a referendum.

It is not inconceivable that the people of Turkey will be soon asked to decide whether their country should again start killing people by court order.

The political game

The government’s preferred route would be to seek the support of the opposition parties – the pro-Kurdish HDP or the centre-left CHP – and win enough support to change the constitution without a public vote.

The HDP is a non-starter: the party is categorically opposed to capital punishment and party spokesman Ayhan Bilgen said just three days after last year’s coup that would not support any parliamentary move to reinstate it.

CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, whose party is the second largest in parliament, has been more coy. Over the past year he has dodged questions on the death penalty with phrases like “let the government present their ideas first” and “it isn’t as if we have been obstructing it”.

The reality is that Turkey’s two biggest parties are playing a game of high-risk chess.

They both know reinstating the death penalty would be electorally popular but have grave consequences for the country’s international reputation. They’re both waiting for the other to blink first and step back.

They’re playing with people’s lives.