In three months, Turkey will hold its last election until 2019. If it actually happened tomorrow, what result would each party be happy with?

AK Party

AK Party

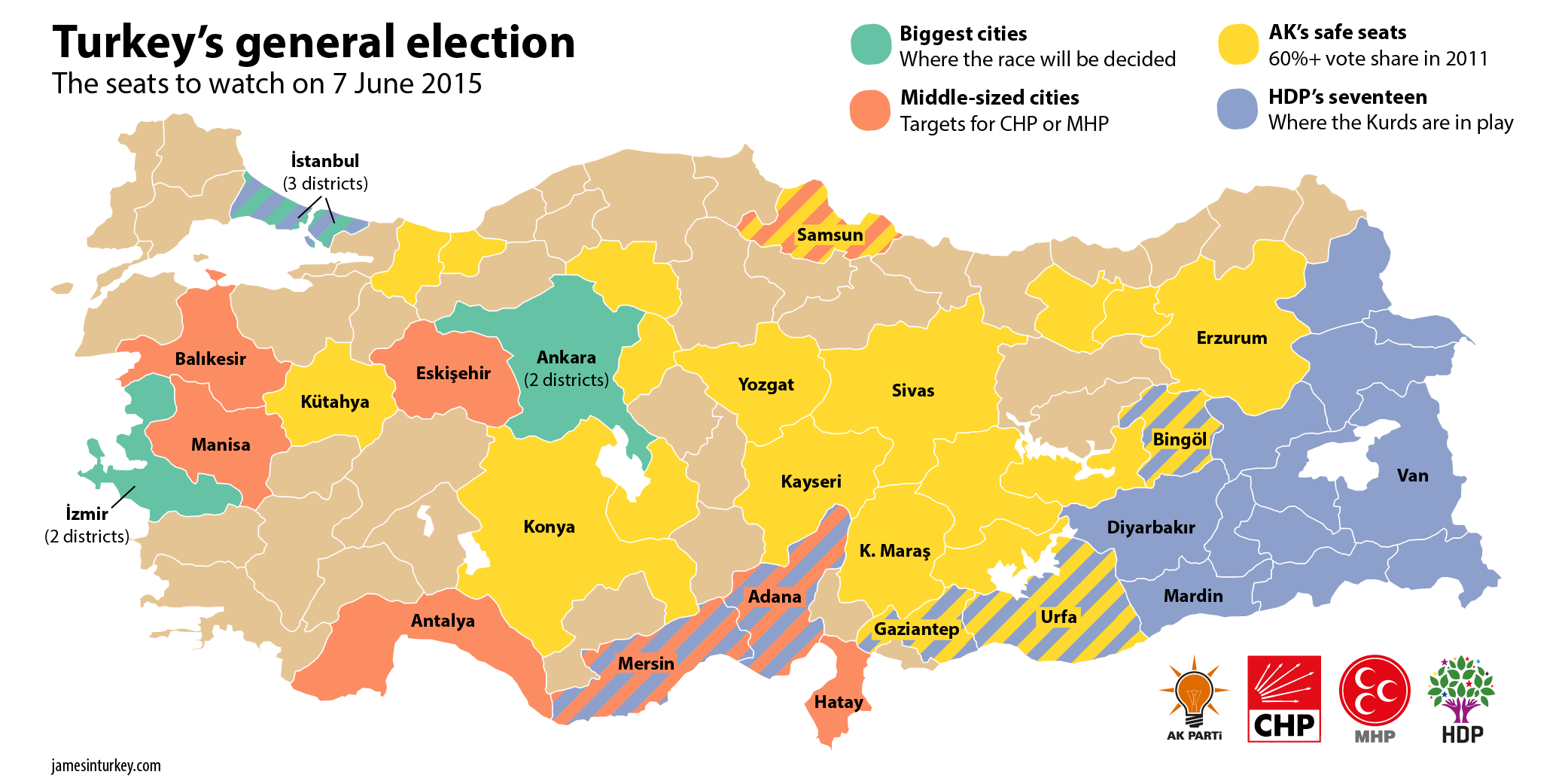

Elections in the 21st century have produced successively more votes and successively fewer seats for the AK Party. This year, Turkey’s governing party wants to sustain the first trend and reverse the latter. But surely this will be election when more people vote for other parties?

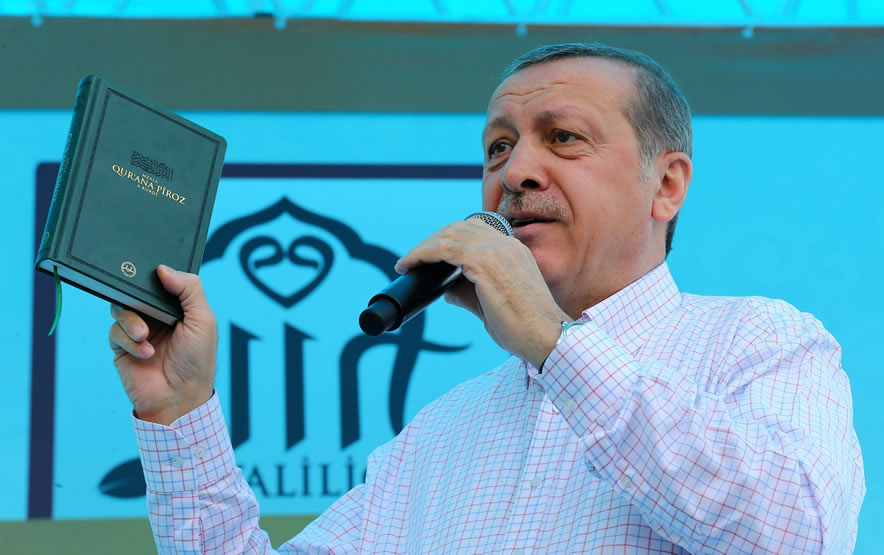

After all, this is AK’s first election under a different leader. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has long made it clear that he won’t be a politically impartial president, but it will be interesting to see how he explicit he is with his loyalties. Shadowy endorsement speeches are one thing, but surely he won’t ride the AK campaign bus or appear in party literature? Opposition parties would leap at the chance to complain to the Constitutional Court.

The AK Party target is to win 367 seats, enough to change the constitution without a referendum. That is nearly impossible with four parties in parliament; lose the pro-Kurdish HDP, and it’s a safer bet.

AK will win – there’s little doubt about that – but it has never been so fractured. Internal support is lukewarm for Mr Erdoğan’s executive presidency plans and there are signs of conflict between the president and his successor as prime minister. A shaky economy, former president Gül’s return to politics and a fledgling, energetic opposition could all unsettle the party and cause an upset.

CHP

No one, not even Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu himself, believes his centre-left party will form a government after 7 June. This is not to disparage him: he has done sterling work reforming the crooked, dogmatic party he inherited as leader five years ago. This new CHP is apparent from the way it now picks candidates: in cities like Istanbul and Ankara, half the nominees will be chosen by party members and not the leadership. It’s a remarkable example of decentralisation.

But the CHP won’t win because the swing in support it needs is too great. There are also dozens of AK Party seats in central Anatolia that simply won’t go to a party of the left.

So what, privately, is the CHP’s target? 2011 was not a bad election for them: they increased their votes and seats, the only party to do both. They took a quarter of the total vote; this time, they will need around one-third to show the party is a developing alternative for government. It will need to build its voter base particularly in Ankara and the Black Sea coast – places where it once did well.

A left-wing challenge from the HDP makes this hard, especially in the big cities. A result that doesn’t build on 2011 will be disastrous for the CHP – and Mr Kılıçdaroğlu’s leadership.

MHP

A slow, under-documented transformation is underway among Turkish nationalists. It’s no longer fashionable to refer to Kurdish people as ‘Turks from the mountain’ and there is loose support for some degree of Kurdish rights. The narrowing of this constituency may have implications for future elections, but for now the country’s nationalist party will command several million votes.

This voter base – pious, socially conservative and mostly male – is easily Turkey’s most homogenous. Your stereotypical MHP man believes more tolerance of religion (read: Sunni Islam) in government has generally been a good thing, but insists Turkey remain a secular country. He is vehement about the Kurds: there can be no talk of a ‘peace agreement’; they should accept the authority of the state.

This makes for great electoral potential in non-Kurdish areas. AK Party voters disenchanted with the peace process or CHP voters seeking a stronger patriotic voice could equally be drawn here. The MHP has the best chance, for example, of eating into AK’s 101 safe seats in central Anatolia.

It is sure to generate MPs from Istanbul, Ankara, and perhaps Izmir, but the MHP has no major ‘stronghold’ region and this could make it difficult to convert votes into more seats. There’s no repeat of talk that it could fall short of the election threshold, though.

HDP

The stakes are highest for Turkey’s fourth party because just a few thousand votes can cause a stark difference in fortunes. Win more than 10 percent, and the HDP could be in parliament with a hefty 50 seats. Fall short, and those seats will go entirely to other parties and potentially feed an AK Party supermajority.

The HDP has shrewdly signed on political heavyweights from across the spectrum, including Celal Doğan and former AK Party deputy leader Dengir Mir Mehmet Fırat. There could be more to come; they can only broaden the party’s appeal.

Leader Selahattin Demirtaş is using his unexpectedly strong performance in last year’s presidential election as a springboard to get his party over the threshold. His approach is two-pronged: first, appeal to left-leaning liberals anywhere in Turkey, whether they are Kurdish or not; and second, reach out to sympathetic voters overseas, who are voting for the first time. It’s an approach that could threaten the CHP in western Turkey; combined with its strong voter base in the southeast, it might just be enough.

The big unknown is the Kurdish peace process, negotiations for which will continue over the next three months. A PKK ceasefire, a grand deal with the government, a change in Abdullah Öcalan’s detention: all these could affect the outcome dramatically.