Turkey’s Kurdish party has ambitiously vowed to contest this summer’s election. It’s a risky decision that pitches the party between riches and desolation

Everyone knows Turkey’s electoral system is a disgrace. It uses the fairly proportional D’Hondt method of allocating parliamentary seats to parties, but imposes a draconian ban on any party that wins less than one in every 10 votes nationwide.

It can mean that a party winning 9.99% percent of votes cast in the country will not take a single seat. So many parties fell short of the threshold in 2002 that nearly half of Turkey’s electorate – 46 percent – was not represented in parliament.

Everyone knows Turkey’s electoral system is a disgrace.

The greatest victim of this barrier has been Turkey’s Kurdish parties, which have traditionally commanded between 5 and 8 percent of the electorate.

For the past eight years they have circumvented the issue by fielding an army of independent candidates, as they are not bound by the 10 percent threshold. The results have been impressive: in 2007, they elected 21 MPs, enough to form a group in parliament. Four years later, the tally rose to 36.

But this year, the tactics are changing. Ever since Selahattin Demirtaş announced they would be running candidates as a party – a first for a Kurdish party in thirteen years – everyone has been asking the same question: can the HDP get the votes it needs?

INTRODUCING THE G17 PROVINCES

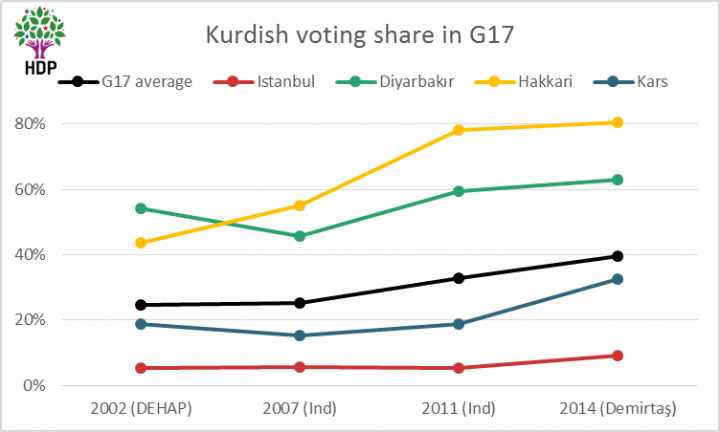

These are the seventeen Turkish provinces where Kurdish parties and candidates have traditionally performed strongest. We’ll call them the Group of Seventeen. Unsurprisingly, most are in the southeast and include prominent cities like Hakkari, Van and Diyarbakır; Istanbul, itself possibly Turkey’s largest Kurdish city, is a notable geographical anomaly.

All the MPs from pro-Kurdish parties we have seen this century came from one of these provinces. The G17 also delivered the bulk of the votes – three quarters – for Mr Demirtaş when he was running for president last year.

We don’t yet know how many people will be registered to vote in this summer’s parliamentary election, but if we assume the electorate grows at the same rate as it did last year, we can estimate there will be around 53,217,629 voters.

Assuming a voter turnout of over 80 percent, the HDP potentially needs 4.5 million votes to cross the threshold as party. Last year presidential candidate Demirtaş took 3.9 million.

The HDP will need to win around 4.5 million votes

MAKING UP THE DIFFERENCE

It won’t be a straightforward question of finding an extra million-or-so votes to plug a gap. Presidential elections are not the same as parliamentary ones and there’s no guarantee that the people who voted for Demirtaş will switch automatically to the HDP.

What is more, the HDP does not hold a monopoly over the Kurdish vote: the governing AK Party is the HDP’s main rival in the G17 and produced 82 MPs from the southeast at the last election.

But there are signs to suggest Mr Demirtaş’s gamble might just pay off: more and more people have been voting for pro-Kurdish parties in recent years. Their share of the vote has increased in every election this century.

The rise is modest in Istanbul but sharp in cities like Diyarbakır, where the past decade has seen much progress for Kurdish rights and freedoms.

The rise is modest in Istanbul but sharp in cities like Diyarbakır, where the past decade has seen much progress for Kurdish rights and freedoms.

And although last year’s presidential election cannot be compared directly to a parliamentary one, Mr Demirtaş’s better-than-expected performance demonstrated his party could appeal to non-Kurdish voters. This will be a key factor in getting his party across the threshold.

Finally, there is a sleeping behemoth in Turkey’s overseas voters, nearly 3 million of them. They don’t elect a French-style overseas representative, but every vote from an expatriate will still bring the HDP a step closer to the 4.5 million votes it needs. There are plenty of Kurds who sought asylum in Europe decades ago who could dust off their Turkish passports and head to their nearest ballot station.

If the HDP falls even a whisker short, it loses everything and gifts the AK Party a supermajority

WALKING ALONG THE PRECIPICE

Nevertheless, the risks are huge. If the HDP falls even a whisker short of 10 percent, all the seats it would have won are allocated under the D’Hondt system to the next biggest party, the AK Party, and this could have serious consequences.

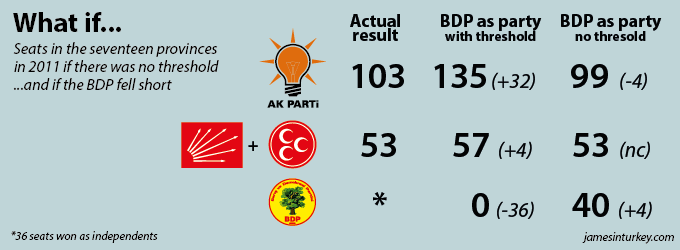

Consider the results of Turkey’s last parliamentary election four years ago in the G17 provinces: the AK Party swept up 103 seats, while the centre-left CHP and nationalist MHP took 53 between them. The remaining 36 seats went to independents who immediately re-joined the BDP, the Kurdish party of the time.

Imagine if the BDP had contested that election as a party and won exactly the same number of votes. If the threshold didn’t exist, it would have won an extra four MPs at the AK Party’s expense. But if the BDP had contested the election with the threshold in place, every vote it received would have gone to waste and its MPs in each province allocated to the next largest party – in most cases, the AK Party.

This is the true injustice of Turkey’s election system: the governing party can sweep more seats than the electorate gave it when a local rival fails to win more than 10 percent.

PAST ELECTIONS TELL A STORY

For a better example of how draconian the threshold can be, consider the result in the G17 provinces following the election 2002, the last time a pro-Kurdish party contested a parliamentary election.

That was a remarkable election when half a dozen large parties – including every single one in the sitting government – failed to cross the threshold in an AK Party landslide. The CHP was the only other party to cross it; the pro-Kurdish DEHAP fell far short, winning a little under 6 percent of the national vote.

As with everywhere in country, the 2002 election divided parliament’s G17 MPs between the two parties: 108 for the AK Party, 59 for the CHP.

But imagine for a moment that DEHAP had somehow managed to collect enough votes from the rest of the country to push it over the threshold. That result would have given it 49 MPs, far more than its “independent candidates” tactic has produced.

This summer, the tally could be even higher.

So you can see why Mr Demirtaş is attracted to running as a party, but it will be a campaign on a knife-edge. Win more than 10 percent, and the riches will be his: he will lead the fourth, perhaps even the third largest party in the next Turkish parliament.

But fall short by just a few thousand votes and he his desolation will not just mean no MPs: he will gift all the seats he could have had to an AK Party supermajority.