It’s happening again.

More than half a decade since the last process petered out, the Turkish government is chattering once more about introducing the country’s first new civilian constitution.

It’s a careful choice of words: “civilian”, because the previous two efforts were brought in after military coups in 1961 and 1982; “first new”, because the republic was founded by civilians in the Ataturk era.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s words this week announcing a revival of the process would have been music to European ears a decade ago.

“By their nature, constitutions must obtain the support of an entire society if possible, but certainly a vast majority,” he told his party’s parliamentary group on Wednesday. “This can only be possible if the new constitution is prepared through a formula that has a place for everyone in the country.”

He went on: “Our preference is for all our political parties to take part in this process. We will demonstrate a sincere effort for this to the end.”

The impossible deal

The trouble is that, unlike a similar all-party constitutional effort that made some progress before falling apart in 2013, Turkey’s opposition parties now do not believe him.

They have been working, quite openly and for quite some time, on an alternative: a cross-party deal that would reverse the executive presidency system introduced four years ago.

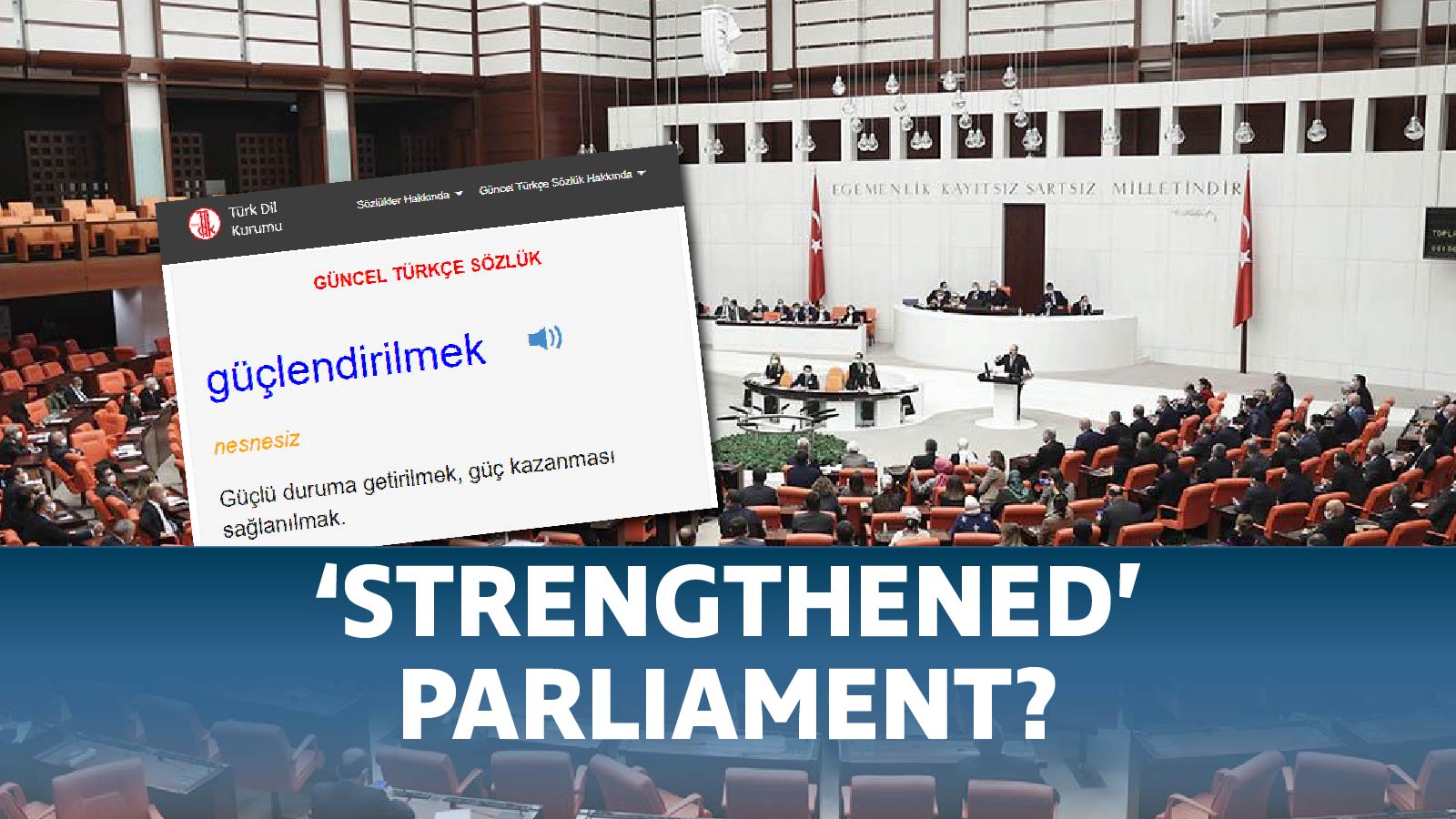

In its place they plan what they call a “strengthened” parliamentary system — but beyond abolishing Mr Erdoğan’s executive presidency and restoring the post of prime minister, there is very little detail publicly available yet.

The opposition’s plans

So far, there are two main documents in circulation:

- “For full democracy, a strengthened parliamentary system” [download PDF] — a proposal from Ahmet Davutoğlu, a former prime minister under Mr Erdoğan who now leads the small Future (Gelecek) Party. He’s been doing the rounds meeting party leaders since November 2020

- “A new system of government for Turkey” [download PDF] — written by Turkish constitutional academics Şule Özsoy Boyunsuz and Berk Esen, this document has been discussed by senior leadership teams in several parties, including the CHP

There is another efforts in the works from Ali Babacan, another former AK Party politician who now leads the Democracy and Progress (DEVA) Party, but no policy document exists publicly for this.

What do the plans say?

There is a lot of overlap between the two documents currently in circulation. Here is what we do know:

The Executive

Both opposition proposals involve restoring the post of prime minister and the concept of collective cabinet government. The presidency would be scaled back to a largely ceremonial role and be elected by parliament, not the public.

| Table #1 | Today's system | Pre-2017 system | Davutoğlu proposal | Istanpol proposal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey's head of state | President | President | President | President |

| Turkey's head of government | President | Prime Minister | Prime Minister | Prime Minister |

| Major decisions signed by | President alone | Cabinet collectively | Cabinet collectively | Cabinet collectively |

| President's duties: ceremonial or executive? ℹ"Ceremonial" Turkish presidencies have always some hard powers, including: appointing and dismissing prime ministers, calling occasional cabinet meetings and a one-time veto on laws passed by parliament | Sweeping executive powers Appointing ministers; passing laws by decree | Mostly ceremonial | Mostly ceremonial with power to veto laws once, but fewer direct appointments | Mostly ceremonial with power to veto laws once, but fewer direct appointments |

The Legislature

Both proposals draw attention to the concept of “constructive no-confidence” — meaning that a majority of MPs can vote to bring down a government only if they also vote to nominate a replacement. This, they say, will help prevent a return to the chaotic coalitions of the 1970s and 1990s.

| Table #2 Can MPs... | The system today | The system before 2017 | Davutoğlu's proposal | IstanPol's proposal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question ministers in person? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Question ministers in writing? | Yes No time limit for a reply. | Yes No time limit for a reply. | Yes Time limits for a reply. | Yes Time limits for a reply. |

| Vote to censure ministers? ℹ"Gensoru" in Turkish | No | Yes | Yes | — |

| Declare 'no confidence' in the government? | No MPs can only unseat the president by calling early elections | Yes A government falls if a majority of MPs vote against it | 'Constructive no confidence' only A government falls if a majority of MPs vote against it AND vote to support a replacement | 'Constructive no confidence' only A government falls if a majority of MPs vote against it AND vote to support a replacement |

| Scrutinise laws by decree (KHKs)? | Very few checks on KHKs | Only certain types of KHK allowed | — | Few KHKs allowed. None can restrict rights and freedoms. |

Elections

Under both proposals, the 10% electoral threshold would be reduced and presidency would last for longer than a five-year parliamentary term. They differ on the details.

| Table #3 Elections | The system today | The system before 2017 | Davutoğlu's proposal | IstanPol's proposal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parliamentary election threshold ℹThe national share of the vote a party must receive before it can win seats in parliament | 10% | 10% | 0% | 5% |

| How is president chosen? | By public once every five years. Two-term limit, with possibility for a third | By the public once every five years. Strict two-term limit. | Elected by MPs for a single, seven-year term | Elected by MPs for one term that is longer than a parliamentary term |

| Can the president be a member of a political party? | Yes | No | No | No |

| Alliances in parliamentary elections allowed? | Yes | No | — | Yes |

| Right to appeal Election Commission (YSK) decisions to another court? | No | No | — | Yes |