Turkey is up in arms about the death of Özgecan Aslan, a 20-year-old university student who was raped and brutally killed in southern Turkey, apparently by a minibus driver.

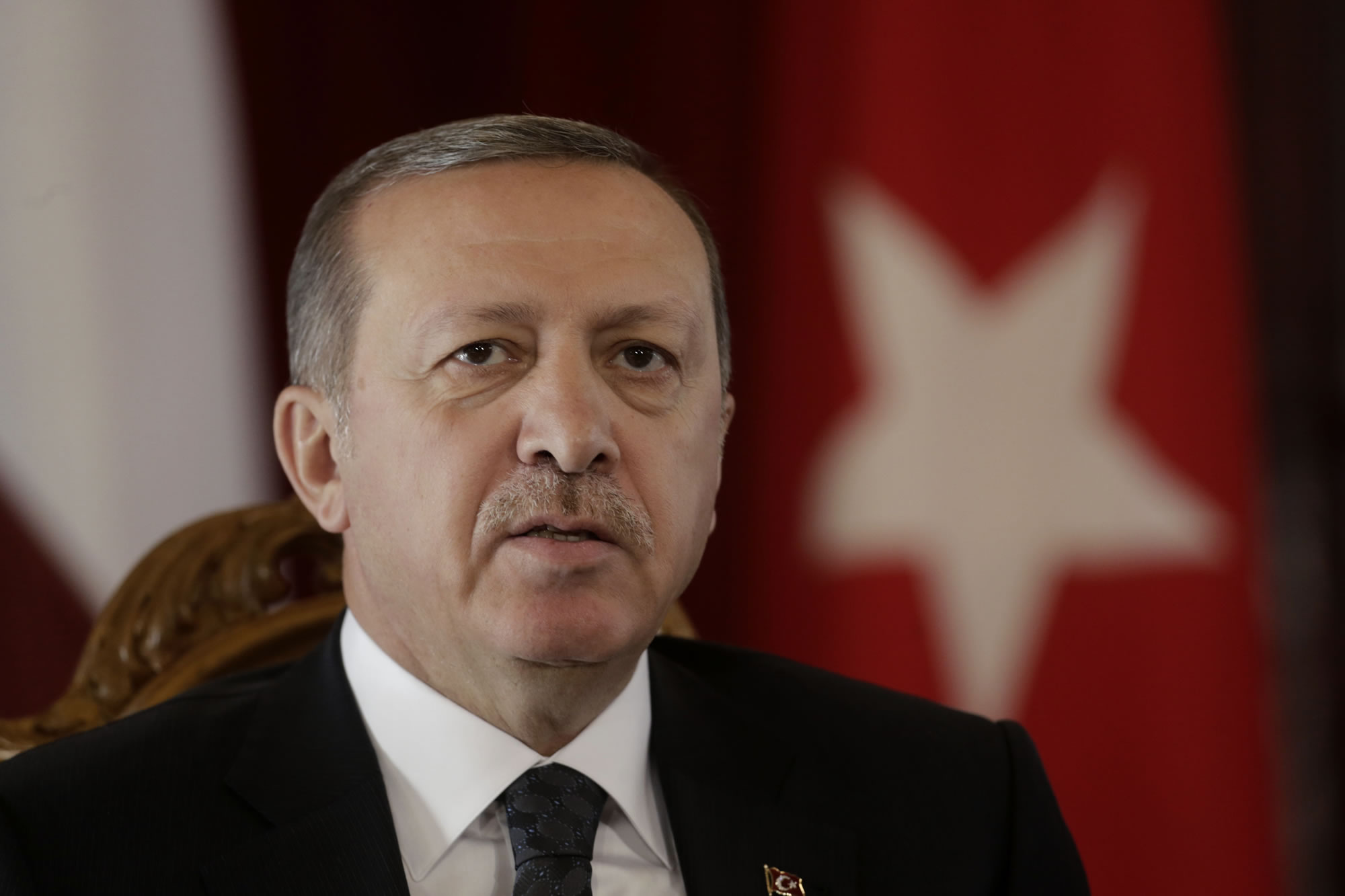

The incident has generated headlines both in Turkey and abroad, particularly as thousands of women took to the streets to demonstrate against violence towards women. At Özgecan’s funeral, the coffin was carried by women only – a rare occurrence for most funerals in this part of the world – and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu were among those telephoning the family to express their condolences.

The case is a gruesome reminder of Turkey’s most shameful problem: not an unfair electoral system or an autocratic president, but the way men treat women. The era of Mr Erdoğan, who never encouraged female employment and bound women to the home by calling on them to have multiple children, bears plenty of responsibility for this.

But tragically, the problem runs deeper than government policy. The notion that a woman’s proper place is in the home, a 1950s chestnut in the west, remains a reality for Turkey.

Of the nearly 29 million working-age people in employment across the country, less than a third (9 million) are women. It isn’t just a question of women being denied work, because the numbers of women and men looking for jobs are roughly the same. An astonishing 20 million working-age women are not counted as part of Turkey’s workforce.

Many, it is true, are students like Ms Aslan. But a crushing majority stay at home: at the last count there were 14 million self-declared housewives in Turkey. Many Turkish men consider it a slight on their honour if their wife works because it suggests they cannot provide for their own family.

Challenging such deep-rooted prejudice takes years, if not generations. But the response to Ms Aslan’s brutal murder has shown that even some of Turkey’s most educated people are prepared to easily discard the principles their country ostensibly is built upon.

The Mersin Bar Association, representing lawyers for the region where Ms Aslan was killed, has collectively declared that none among their number will defend the murder suspect in court. The bar clearly feels it is important to tell the world that it does not condone the crime.

But the bar has it wrong: no reasonable person takes the opposite view, and by refusing to defend the suspect it is jeopardising a fair trial. Turkish society has decided the minibus driver is guilty and that a trial is a mere formality, and lawyers have succumbed to that view. That is truly troubling.

Even more alarmingly, senior members of the Turkish government appear to have decided what to do with the man everyone knows is guilty.

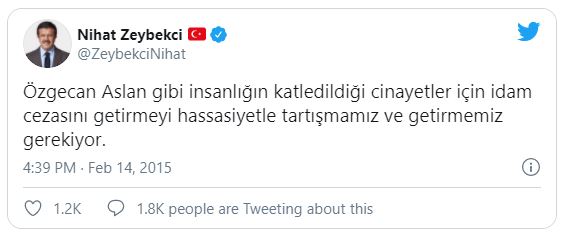

Economy minister Nihat Zeybekçi tweeted: “we need to discuss and introduce with sensitivity the death penalty for murders where – as with Özgecan Aslan – humanity is massacred”

Turkey abolished the death penalty more than a decade ago to conform with European Union law. Comments like Mr Zeybekçi’s suggest people don’t understand why Europe itself scrapped the penalty. Polling often finds a majority of European people in support of reintroducing the death penalty; it is the role of government to explain why the abolition is in place, not to encourage populist chatter.

Back in 2011 I wrote about a newspaper’s decision to start a national conversation on marital violence by publishing a photograph explicitly depict the knife murder of a woman. I wrote then that there was a “deeply conservative streak in Turkish society that promotes the family unit over the individual” and that the greatest victim of this approach are women. Has anything changed in four years?