The nationalists hold the key to Turkey’s first coalition government this century. They want to throw it away.

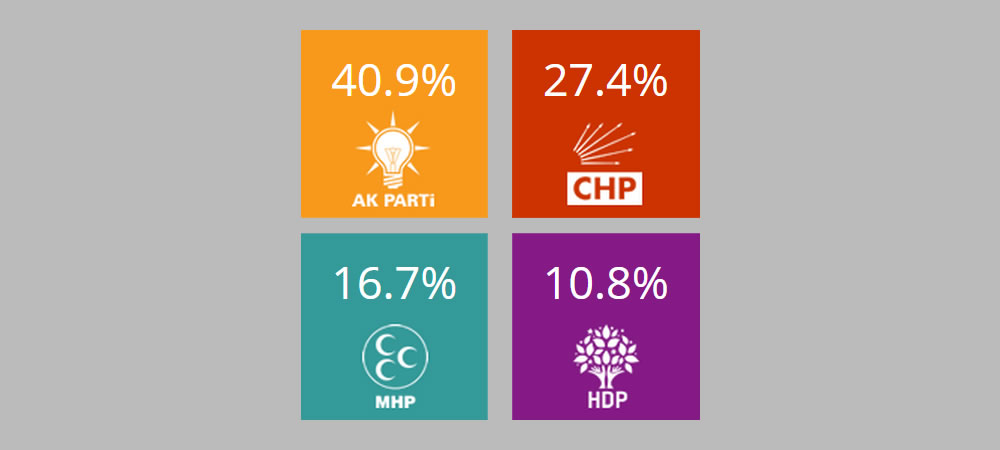

The AK Party shed votes and seats aplenty at this election, and not all of them to conservative Kurds: the nationalist MHP chipped away at many of the AK strongholds in central Anatolia, where conservative voters hold sway.

The result restores Devlet Bahçeli’s party from the knocking it took at the last election. The MHP has three percent more of the votes, 20-odd more seats, and is now a key player as the parties prepare to haggle over a coalition.

But there is a problem: Mr Bahçeli isn’t interested. He held a 1am press conference last night to tell bleary-eyed reporters that President Erdoğan should “think about” resignation if he’s going to continue being a partisan president. He then permitted a single question – inevitably about the MHP’s coalition preferences – and essentially said he preferred not being in one.

Issues galore

In Mr Bahçeli’s defence, he is in a tricky spot. Of the three other parties he could get into bed with, he has beef with two of them.

By nature, Turkey’s nationalists have a huge problem with the pro-Kurdish HDP – separatists who want to divide the country, in their view. The MHP manifesto explicitly says it will oppose any arrangement for increased minority language rights and devolved government – all key components of the HDP shopping list.

The AK Party aren’t happy bedfellows either. MHP’s entire election campaign was built around the word “remember” – remember the corruption, the unemployment, and the economic inequality of the AK Party years. Can Mr Bahçeli really stomach an alliance after all that?

That leaves the CHP. There is plenty of precedent for these two parties getting along – a joint candidate in last year’s presidential election, to begin with – but the electoral maths just doesn’t work. The CHP is projected to have 132 seats; with the MHP’s 80, they are still some way short of the 276 they need for a majority.

Not for me, thank you

Coalitions are always difficult deals. If they weren’t, the people involved would all be in the same party. This election has left the nationalists as kingmakers: they are ideologically aligned to AK and have common cause with the parties that want to kick AK out.

But judging by his comments yesterday, Mr Bahçeli is quite content to shun both options and stick around in opposition. Let the AK Party and HDP come to a deal, he says, or let the AK Party, CHP and HDP band together. He would much rather stay in opposition and contest an early election in a year or two.

The attitude is astonishing, and not just because Mr Bahçeli appears to be that rare breed of politician who wants to keep as far away from power as possible.

The oscillating MHP vote share shouldn’t fool anyone: this is a party with a limited voter base. There are plenty of conservative-minded voters – overseas, for example, where the party came a very poor fourth – who shudder at its unrefined nationalism.

The MHP needs reform, not obstinate obstructions. A spot of coalition compromise would make a great rehearsal for that.