On a phone?

This page is best viewed in landscape mode

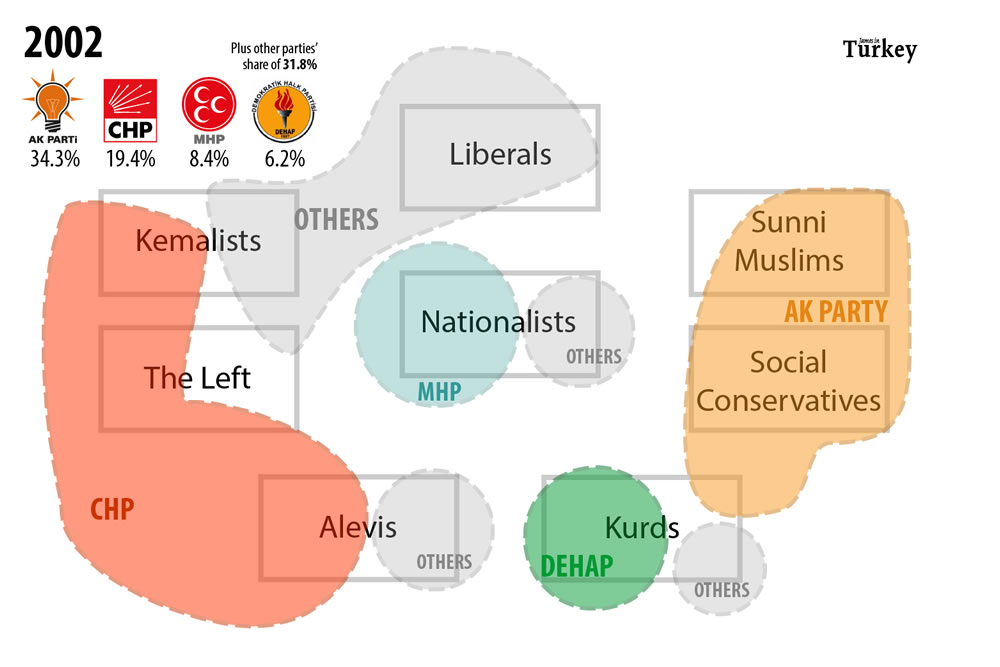

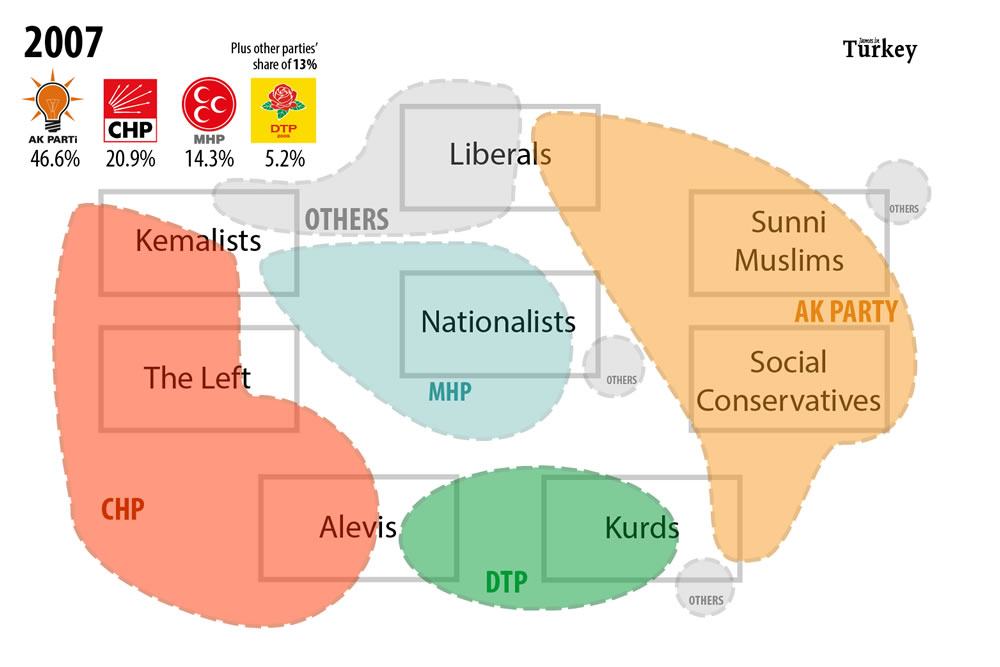

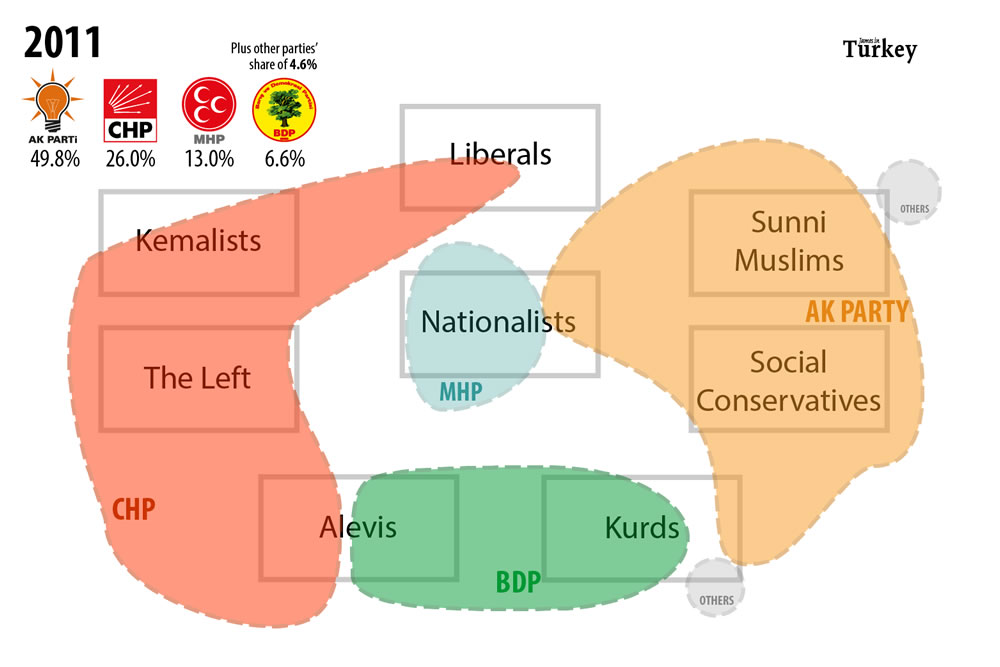

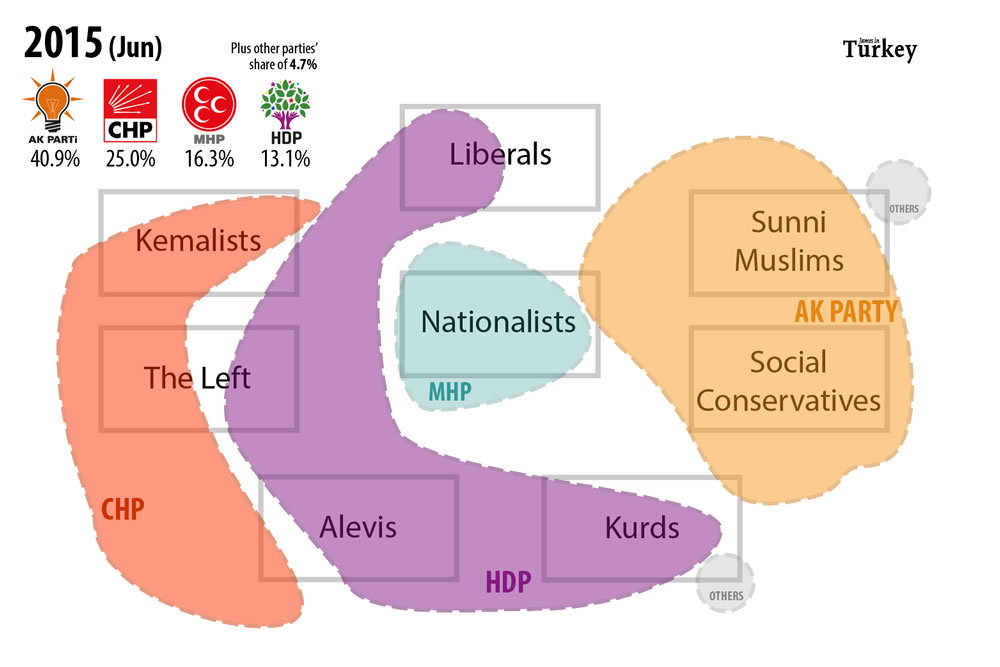

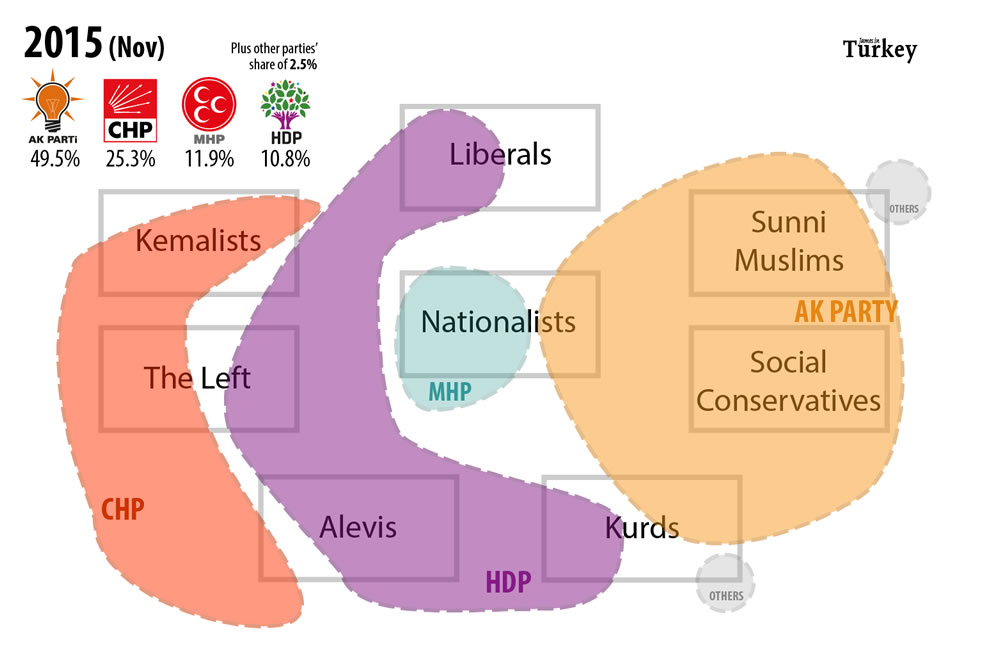

Any election that is genuinely competitive involves shifting voter loyalties where parties compete for the support of groups that did not vote for them last time around. Turkish elections are no different.

But what are these groups in Turkey and how have they voted in the past?

What follows is a heavily simplified series of charts that helps to illustrate how shifting party loyalties among certain voter groups shaped Turkish elections since 2002.

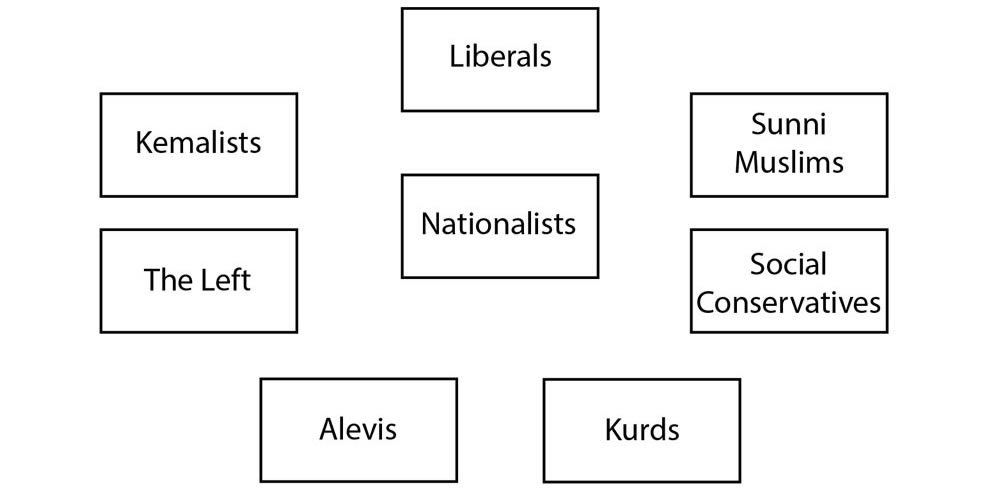

Inspired by Venn diagrams, it places voters in eight broad categories and illustrates how political parties appealed to different combinations of them in different elections.

Here are the voter groups we’ll be using:

A few disclaimers:

- These groups are not equally-sized. There are far, far more socially conservative people in Turkey than liberals, to name just one example.

- They are not mutually exclusive, either: it is entirely possibly for individual voters to identify themselves with two, perhaps three categories.

- And of course, there are other voter groups not illustrated here.

That said, it is a useful tool to explain voting patterns in recent elections and to understand how the parties are positioning themselves in the 2018 election.

Pick an election year to get started and scroll down for some commentary: