A television programme brings Turkish-Israeli relations to a newer low

Such was the anger of Israeli deputy foreign minister Daniel Ayalon that he decided to pull a bit of a stunt. To demonstrate his disapproval of the portrayal of Israelis in a dodgy drama on Turkish television, he summoned the Turkish ambassador to Tel Aviv to his office.

He deliberately kept the ambassador waiting in the corridor, in full and awkward view of the waiting cameras. Once ushered inside, the ambassador was seated on a low sofa while ministry officials towered over him opposite. Placed on the coffee table between them was a solitary Israeli flag – no Turkish one alongside it, contrary to diplomatic convention. All done to implicitly shame the ambassador and convey the displeasure of his hosts over a certain issue.

Done well, a rebuke of this kind can be rather effective.

But Mr Ayalon got it wrong. His departure from subtlety – he pointed out the height difference and absent flag to the gathered reporters – was where his rebuke became an insult. Israeli television carried the footage on Tuesday; nearly every Turkish newspaper carried Mr Ayalon’s behaviour on their front pages on Wednesday morning. All, from the fiery Vatan to the level-headed Radikal, were outraged.

Mr Ayalon used to be Israel’s permanent representative to the United Nations, a man not unfamiliar with the subtleties of diplomatic protocol.

He is also a masterful performer: when I saw him speak at the London School of Economics last October, he was placid in the face of the loud abuse he received from pro-Palestinian members of the audience. The heckling prevented any reasonable debate, which also helped him disguised his more controversial policies.

Why he got it quite so wrong with the Turkish ambassador is a mystery to me.

Lowbrow drama

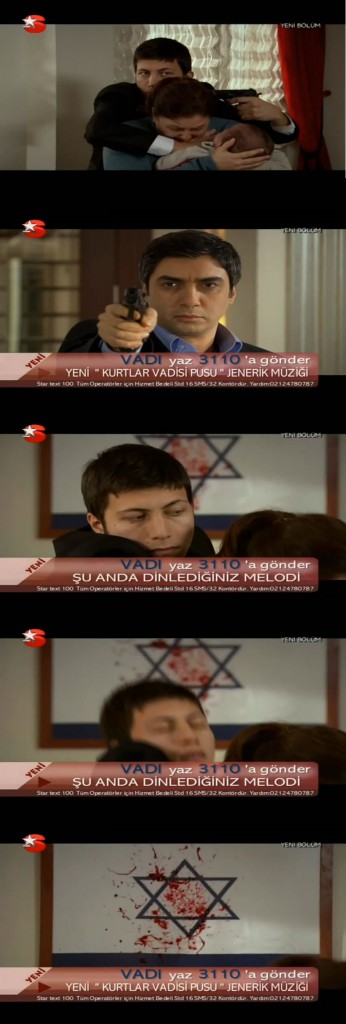

The television programme, Valley of the Wolves: Ambush is a lowbrow mafia drama, popular for its protagonist Polat Alemdar, a gun-wielding secret service agent fueled by a love for his country and no small amount of testosterone.

The offending episode, broadcast in December, shows him infiltrating the Israeli embassy, where Mossad agents are holding a Turkish child they’ve abducted to take back to Israel and convert to Judaism.

The perpetrator, surrounded, takes the child hostage, but is killed by a bullet through the head. Blood splatters onto the Israeli flag hung conveniently on the wall behind him. The impact of the crucial blood-on-flag moment was lessened somewhat by an on-screen advertisement encourage viewers to download the series’s background music as a ringtone.

In principle, the diplomatic summons was entirely reasonable. Had it been Israeli television showing Turkish agents abducting children and having their blood splattered on the Turkish flag, the Israeli ambassador to Ankara would have been summoned to have his knuckles rapped in quite the same way.

Hampered mediation chances

In practice, however, the episode has injected further tension into the already icy relationship between Turkey and Israel.

There are two causes for concern:

Firstly, the degenerating relationship between the countries is not a good thing, neither for Israel, nor for the Middle East process, nor for Turkey’s newfound courage as an emerging regional power. Reports suggest Turkey was previously very close to brokering a peace between Israel and Syria; Israel now refuses to accept Turkey as a mediator.

Second, Turkey’s increasingly anti-Israel tone is driven to largely by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

The current mood began with Israel’s attack on Gaza last year and the Turkish prime minister’s infamous walkout from a debate on the situation during the Davos Economic Summit. Mr Erdoğan exchanged harsh words with Mr Peres during that debate, has been outspoken on Israeli actions ever since, and has led Turkey into closer ties with Iran, Lebanon and Syria.

Latent intolerance

But there is more to Turkey’s Israeli stance than Mr Erdoğan’s views. Last year the director of a culture association in Eskişehir attracted headlines when he placed a notice outside his centre that read “Dogs are free to enter this building” above another: “Jews and Armenians may not enter.”

The director said his move was in response to an Armenian citizen who allegedly hung a similar notice on his door banning dogs and Turks. What was worrying about the incident was that the director’s decision to include the word “Jew” appeared to be unprovoked.

The Valley of the Wolves episode is another such incident that appears to indicate latent feelings of casual antisemitism are becoming more prominent in certain sections of Turkish society.

Most Turks would be horrified at the idea of insulting members of another faith – indeed, Mr Erdoğan himself criticised the Eskişehir director and said it was wrong for “one group of citizens in this country to stand up and provoke another group of citizens.”

But in a society where high profile Jews are few and far in between, and where ordinary Jews keep a low profile, such antisemitism does go unchallenged.