There are two proposed two options to reform Turkey’s election system, but as our leader piece argues both options would simply entrench his AK Party’s position. Here is our analysis to explain why.

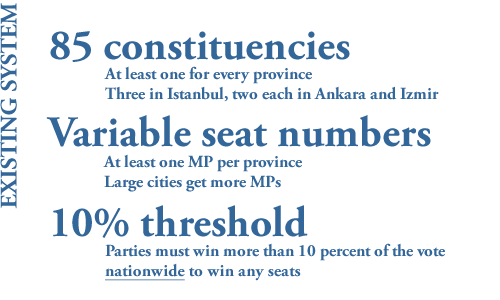

How do things work today?

The existing system has been in place since 1982, when the post-coup constitution was approved, and has only been slightly tweaked along the way. Each of Turkey’s provinces is an electoral district (constituency); Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir are further divided to account for their size as the country’s largest cities.

The number of seats allocated to each constituency changes according its population and is reviewed every other year. Larger provinces naturally get more seats, but every province, however small, must have at least one member of parliament.

A distinguishing and ruthless feature of Turkey’s system is its election threshold, which at 10 percent is the highest in Europe. Parties with a vote share lower than this are not represented in parliament at all, even if they are overwhelmingly popular in a small number of seats.

As part of his recent package of democratic reforms, Mr Erdoğan announced three options for electoral reform he would to like to debate. One of them would be in place in time for the 2015 general election, he said. The options are:

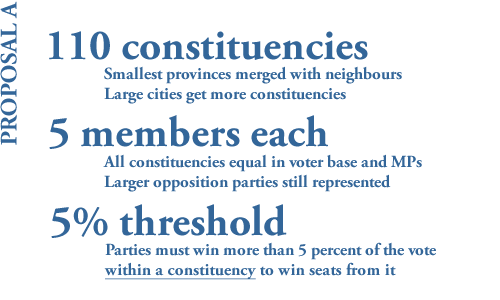

a) Creating 110 five-seat constituencies and a 5% threshold in each of them;

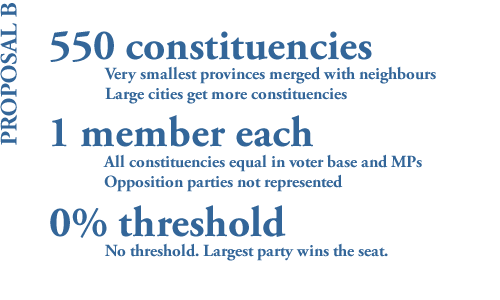

b) Creating 550 single-seat constituencies with no threshold; or

c) Retaining the existing system unchanged.

What is he proposing?

How would they work?

To try and understand how both proposed systems would work, let’s take the results from Turkey’s most recent election. This post will look at how they change the results in four different types of Turkish province:

- Part of a metropolis (the first electoral district in Istanbul);

- A big city (Adana);

- A stronghold for the main opposition (Tekirdağ); and

- An eastern rural province (Iğdır)

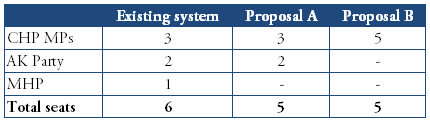

Istanbul’s first electoral district

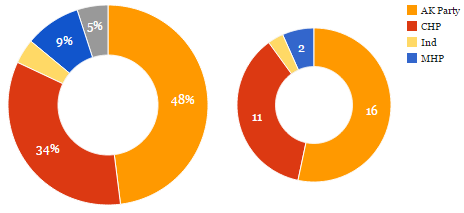

Istanbul-1: parties’ share of the vote (left) and elected MPs (right)

Turkey’s three largest cities – Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir – each have more than four million people living in them. Together, they account for a third of the country’s population, which is why many political parties have focused campaign efforts here more than anywhere else.

Istanbul is by far the largest of these, divided into three electoral districts of between 27 and 30 MPs each. The first district, shown in the map below, covers the whole of Anatolian Istanbul. The second and third districts are wholly on the European side of the province.

The image above shows each of Istanbul-1’s 278 neighbourhoods in the colour of the party that won them in 2011: a sea of AK Party yellow with pockets of CHP red. Dark blue – the colour this blog uses for the MHP – is nowhere in sight because the MHP did not win a single neighbourhood in Istanbul, let alone a district. This accounts for why the existing system produced only two MHP MPs and one independent in Istanbul-1 .

Proposal A would divide Istanbul-1’s 278 neighbourhoods into seven constituencies electing five members each. Proposal B would create 37 single-member districts. If either system were in place in 2011, a majority would have been taken by AK Party candidates and the remainder by the CHP. No MHP or independent MP would emerge, despite a third of a million people voting for one.

The real problem is how to divide Istanbul’s Asian side into constituencies. Take proposal A. If we were to assume each constituency needed to represent around 450,000 voters, the central district of Kadıköy (440,029 registered voters) fits the bill quite neatly.

The distant Black Sea district of Şile (21,667 registered voters), on the other hand, would need to be merged into a neighbouring district. Nearby Beykoz (179,347 voters) is a good idea, but the combined total is still not enough. But combining those two into next door Ümraniye (420,745 voters) pushes us far over the threshold. That means neighbourhoods inside districts will need to be broken up.

Worse, the divisions can get political. Suburban Maltepe (329,817 registered voters) was evenly split between the AK Party and CHP at the last election and it isn’t quite large enough to be a constituency on its own. Merging it with next door Sancaktepe (169,839 registered voters) might make sense mathematically, but it was solidly won by AK and a combined constituency would be tipped towards them.

Istanbul-1’s 2011 results under proposed systems

Conclusion: In a heaving Turkish metropolis, either of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s proposed electoral reforms would wipe out small party representation. But drawing the boundaries will be a tricky and controversial business.

Adana

The MHP did poorly across Turkey in 2011, but its performance in Istanbul was particularly lacklustre. But what about a province where it did marginally better, such as Adana?

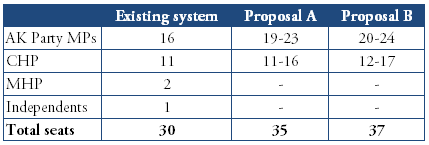

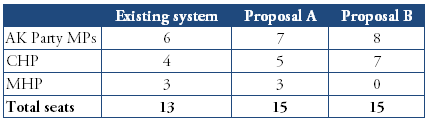

Adana: parties’ share of the vote (left) and elected MPs (right)

This is Turkey’s fifth largest province with more than a million registered voters. In 2011, it was won by the AK Party, but not overwhelmingly; the CHP took some inner city and coastal districts. Under the existing system the thirteen seats were shared by all three parties: six MPs for the AK Party, four for the CHP and the MHP, three.

Both of Mr Erdoğan’s proposed systems would delivered Adana two extra MPs. Under the five-member constituency system, proposal A, this would make for three electoral areas:

- Seyhan, an inner-city district; (AKP 2 MPs, CHP 2, MHP 1)

- Çukurova, Karaisalı, Sarıçam and Yüreğir, which make up Adana’s other Büyükşehir districts; (AKP 2, CHP 2, MHP 1) and

- Rural Adana (AKP 3, CHP 1, MHP 1)

Under the single-member constituency system, the MHP would not win a single MP. The spoils would be shared by the AK Party and CHP, depending on where the boundaries are drawn.

Adana’s 2011 results under proposed systems

Conclusion: Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s proposed electoral reforms would increase the number of MPs in a large Anatolian city, but would mostly benefit the two largest parties.

Tekirdağ

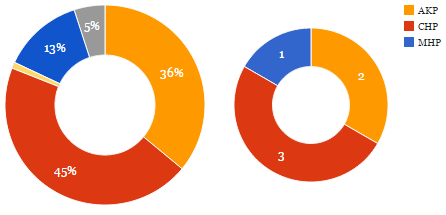

The European portion of Turkey outside of Istanbul is a CHP stronghold and Tekirdağ is no exception. Mr Kılıçdaroğlu’s party took all but one district at the last election, with that margin giving them half of the province’s six members. The AK Party and MHP shared the remaining three.

Tekirdağ: parties’ share of the vote (left) and elected MPs (right)

Both of Mr Erdoğan’s proposals would reduce Tekirdağ’s representation by one MP. Voting is pretty consistently CHP in this province and AK Party and MHP voters are not concentrated in any particular area. Under the proportional voting system of proposal A, the reduced seats would mean the MHP would lose its member.

Under proposal B, which is not envisaged to be proportional, the province would lose its AK Party members too, with all five seats going the CHP.

Tekirdağ’s 2011 results under proposed systems

Conclusion: Provinces like Tekirdağ show that the prime minister’s proposed electoral reforms do not benefit his AK Party directly but whichever party is dominant in a province. The trouble is that his AK Party is dominant in most provinces.

Iğdır

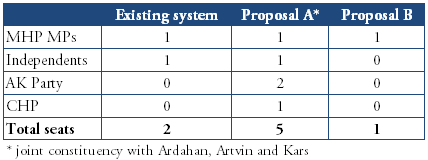

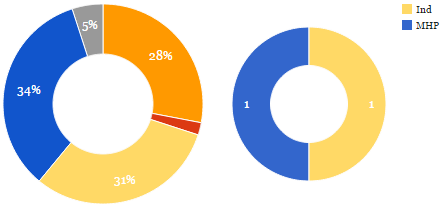

The only province won by the MHP in 2011 was a small one in the far east of the country.

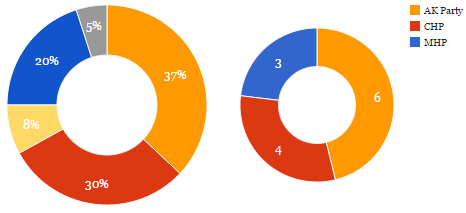

Iğdır: parties’ share of the vote (left) and elected MPs (right)

Tiny Iğdır has a population of 100,000, which gives it two seats in parliament. It is far too small to be a constituency of its own under proposal A; in fact, it would need to merge with as many as three neighbours to become large enough. Combining it into Artvin, Ardahan and Kars should create a large enough constituency to meet the 450,000 voter threshold, but these voters would be represented by 5 MPs, a significant loss on the nine MPs the four provinces elect under the existing system.

Under proposal B, Iğdır is large enough to be a constituency on its own, but with one fewer MP than at present. This would mean that in 2011 Iğdır would have one MHP MP and the independent Pervin Buldan would not have been elected.

Iğdır’s 2011 results under proposed systems

Conclusion: Small provinces where people vote against the national trend are likely to be swallowed up by larger, more mainstream neighbours under the prime minister’s first proposal. The second proposal can create truly localised representation for such provinces, but there will still be fewer MPs to elect.