There’s plenty of speculation out there on the implications of the last eleven days for Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s political future. The Economist called this week for him to step down next year and make way for President Abdullah Gül. Ben Judah argued in the Financial Times that the prime minister needed to see this as his “1968 de Gaulle moment”. Others have said any Erdoğan departure would lead to the immediate implosion of his Justice and Development (AK) party and the splintering of his centre-right/conservative/moderately Islamic coalition.

Perhaps. I will freely admit I am not in a position to guess what will happen next. No-one is, really. Right now, events on the ground feel a little like a swinging pendulum: first there was the calm when the police withdrew from Taksim, then there were the clashes in Beşiktaş. We then had the widely-publicised apology from deputy prime minister Bülent Arınç, but the pendulum swung back after we saw a greater police crackdown in Ankara.

There were more protests last night, but it was also the most peaceful night we have seen since the disturbances began almost a fortnight ago. The protesters are not blinking; neither, judging by his defiant 3am rally last night at the airport, is the prime minister.

Over the coming days, I will try and consider the more plausible scenarios for Mr Erdoğan’s future. I begin by examining the AK Party’s solid electoral foundations.

Everybody knows the AK Party won just shy of fifty percent of the vote at the last general election in 2011. What everyone doesn’t know is how that vote is spread across the country. Kindly consider the map below, which should magically reveal nuggets of information as you tap it. Doesn’t work? Try clicking it instead.

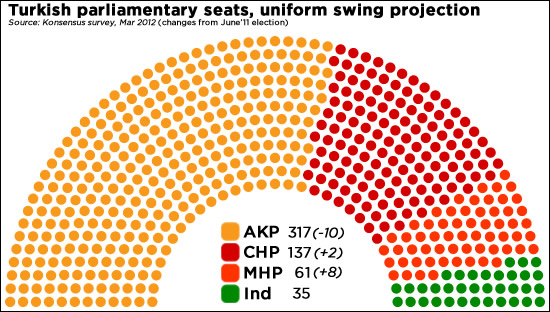

[embedit snippet=”swiffy1″]The Turkish provinces highlighted in AK yellow represent those where the AK Party not only came first, but won it with more than sixty percent of the vote. Turkey’s D’Hondt electoral system means that in the larger provinces, AK won the majority of seats; in the smaller ones, they swept them all. In 2011, this made for a total of 102 seats – nearly a fifth of all the seats in parliament, and nearly a third of their total haul of 327.

These 21 provinces are Anatolian and conservative. Most are largely rural. They are not very Kurdish either. They will have voted True Path (DYP) or Motherland (Anavatan) before AK, and Justice (AP) before then, and Democrat (DP) before then. They are firm ground for a parliamentary majority.

Forget Istanbul or Ankara; these are the AK party’s true safe seats.