This briefing last updated 19 December 2022.

There is a short answer to this question: yes, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan can run for another term despite the constitution’s two-term limit, provided he seeks it before 18 June 2023.

The longer answer is entangled in the complexities of Turkey’s constitution and the amendments that were endorsed in a disputed referendum in 2017.

Here’s the story as briefly as I can possibly tell it.

Article 101 of Turkey’s present constitution is an eight-paragraph behemoth that describes how a president becomes a candidate and is elected. The crucial line is in paragraph 2:

The President of the Republic’s term of office shall be five years. A person may be elected as the President of the Republic for two terms at most.

In Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s case, he was elected to his first term on 10 August 2014. He didn’t serve a full first term because early elections were called on 24 June 2018, which Erdoğan won. This was the start of his second, and final, five-year term.

So far, so clear.

But things are complicated by Article 116 of the same constitution, which states (paragraphs 1-3, emphasis added by me):

The Grand National Assembly of Turkey may decide to renew the elections by three-fifth majority of the total number of its members. In this case, the general election of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey and the presidential election shall be held together.

If the President of the Republic decides to renew the elections, the general election of the Turkish Grand National Assembly and the presidential election shall be held together.

If the Assembly decides to renew the elections during the second term of the President of the Republic, he/she may once again be a candidate.

The crucial point, therefore, is in who calls the election.

The 2017 referendum introduced a double-jeopardy system where either parliament or the president could call an election, but elections for both have to be held simultaneously.

This creates the bizarre situation where Erdoğan can call fresh elections if he chooses, but choosing to do so will invalidate him from standing as a candidate for president.

However, if parliament — the Grand National Assembly of Turkey — were to call the election, Erdoğan can be a candidate. The rationale behind the law was to prevent parliament, if it were controlled by a party other than the president’s, from using term limits as a means to unseat the president.

But it also means that if the president’s party does control parliament, that president could notionally seek a limitless number of additional terms

What it means for today’s purposes is that if Erdoğan wants a third term as president, he has to instruct his party to call an election. He can’t do it himself.

So what if an election is called before June 2023?

This seems to be the fail-safe route to a third Erdoğan term. University entrance exams, ordinarily scheduled on a Sunday for the middle of June, could offer a reason to bring the election day forward by a few weeks

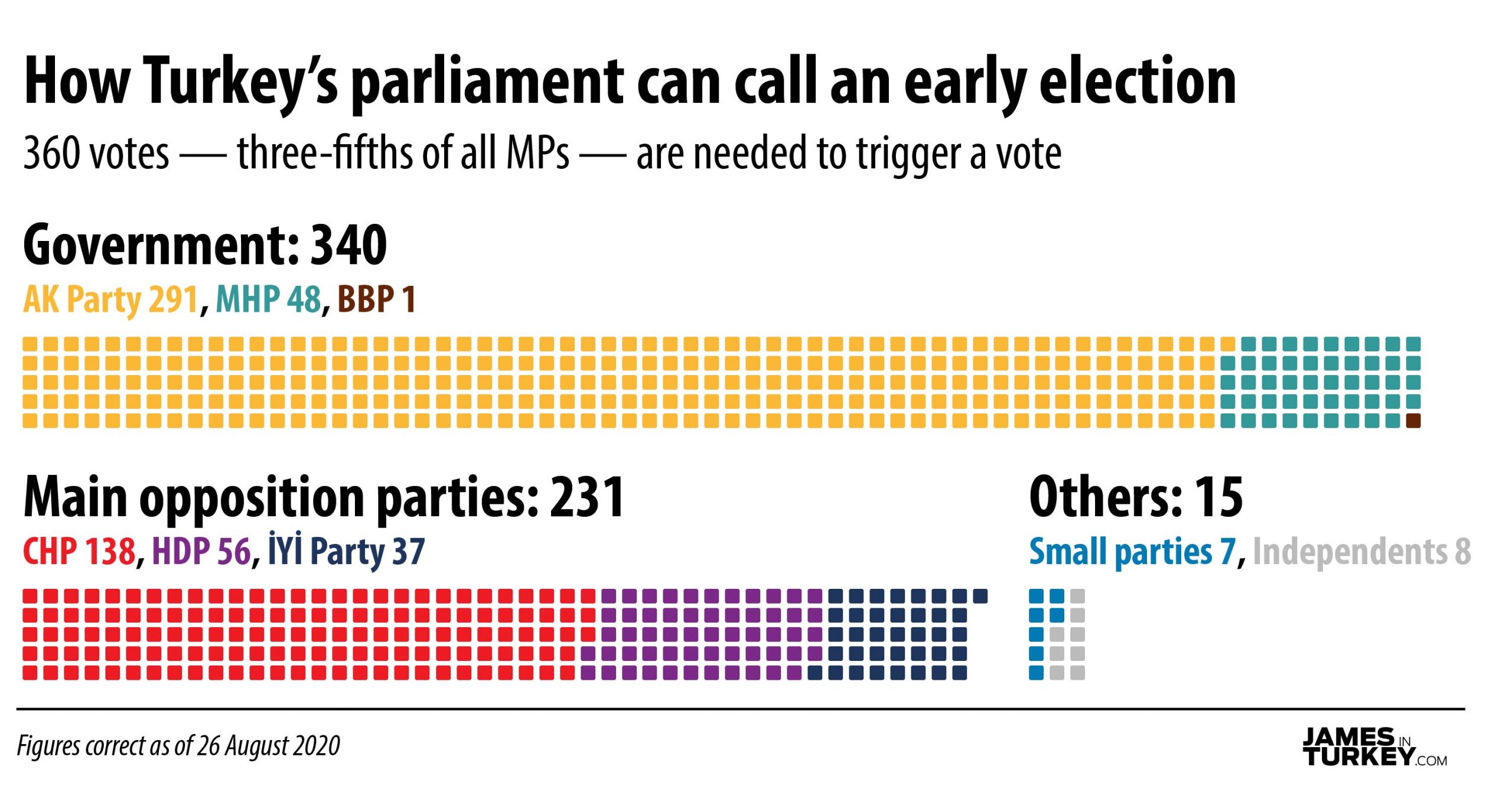

Under Article 116 (above), three-fifths of MPs need to vote to call an early general election. That means 360 MPs in the 600-seat chamber.

The governing AK Party currently holds 291 seats while its de facto coalition partner, the MHP, has 48. The BBP, a minor party, brings an extra seat, taking the total to 340, 21 short of the number needed.

So the AK Party will need to turn to the opposition for support. There are three parties — CHP (138 seats), HDP (56) and IYI (37) — that could get them over the line. If they do, Erdoğan can run for a third term.

Would the opposition help them out here?

It’s not impossible.

On the one hand, there is the fact that opposition parties wouldn’t want to support a government bill of any sort.

On the other hand, refusing to support an election could play into the government parties’ hands. Any opposition party worth its salt wants power, and the only way to get it is an election, so they would need a mighty good reason to actively vote against one.

The likeliest scenario is that the opposition parties will support a bill for an early election, but might attempt to seek concessions — over scheduling, for example.

What happens to Erdoğan if elections are held on time?

This is looking increasingly unlikely, but: if no election is called before Sunday 18 June 2023 and the constitution has not been amended again, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s second and final term would expire that day.

Unless, that is, no presidential candidate wins more than 50% of the vote in the election on 18 June. In that case, a run-off vote must be held on Sunday 2 July 2023 and Mr Erdoğan gets to stick around for another fortnight.

Wait a second. Isn’t Erdoğan actually on his first term?

Some supporters of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan have voiced this argument — that he was elected to a new and different job in 2018, because the constitutional changes of the previous year had essentially fused the presidency’s ceremonial duties with the prime minister’s executive responsibilities.

They argue his first term expires in 2023.

Opponents point out that the fundamentals of the position are unchanged: the job title is the same, it is still Turkey’s head of state and its term limits haven’t been altered in 13 years.

Yet the AK Party did originally seek to draw a difference between the old job and the new by changing the Turkish name of the post from cumhurbaşkanı to başkan. The difference between the two words is subtle: both words translate into English as “president”; başkan carries clearer connotations of executive power. It is the Turkish word used for the President of the United States, for example, whereas ceremonial presidencies like Germany are usually called cumhurbaşkanı.

But the AK Party ended up dropping başkan from its proposals during its pre-referendum negotiations with the nationalist MHP, which demanded cumhurbaşkanı be retained.

There is a bit of ambiguity on this matter, but it’s worth noting the following points:

- There is no reference anywhere in 2017 AK Party/MHP reforms that says the reformed post of cumhurbaşkanı is new, or that the original role of cumhurbaşkanı is now defunct;

- Recep Tayyip Erdoğan himself has not openly said where he falls in this debate. He has not commented on whether he is serving a first or second term, and has parried any question on his plans to stand at the next election. If he decides he can stand and his opponents tell him he can’t, it would create strong campaign fodder for him;

- Clearly, legal ambiguities like these must be cleared up by Turkey’s constitutional court — but opponents will say its judges will face undue pressure to rule favourably on a matter concerning Mr Erdoğan’s political future.

There’s a fight brewing here.